Avoiding verification brittleness in Dafny

What is brittleness?

Dafny is designed to integrate programming and verification, allowing you to write both programs and specifications in the same language. To show that the code meets the specification, you may also need to annotate the code with the outline of a proof, such as including an invariant on a loop. To complete the verification process with only these hints available, Dafny relies on automated theorem proving using an SMT solver. These solvers allow for much of the verification effort to be performed automatically. However, SMT-based automation can come at a cost. If you rely too much on automation, you may find that the outcome of verification becomes chaotic. A particular proof goal may fail to verify after seemingly unrelated changes such as upgrading to a new version of Dafny, adding an unrelated definition to your development, or even changing the name of a variable. This issue is sometimes referred to as brittleness.

Fortunately, brittleness can usually be avoided through the application of common software engineering principles such as modularity and abstraction, and by structuring proof annotations to guide the SMT solver more precisely. In this post, we will dig into how to avoid brittleness in practice, what properties of a program tend to push it near this problematic threshold, and how to write Dafny code that consistently verifies. To begin, let’s consider an example program that is specifically designed to exhibit the problem. We’ll start by defining a type of rational numbers.

ghost predicate Rational(x: real) {

exists n: int, m: int :: m > 0 && x == (n as real) / (m as real)

}

type rat = x: real | Rational(x) witness (0 as real / 1 as real)Although this definition is relatively simple, it uses an existential quantifier in the predicate defining the subset type rat, which causes existential quantifiers to be part of almost every query sent to the SMT solvers. This is something that such solvers are notoriously bad at reasoning about. We’ll show that this does indeed cause trouble at first, but that it’s possible to resolve that trouble, resulting in a version that consistently verifies.

To see the issues that arise, let’s try to write a function to add rational numbers.

ghost function add(x: rat, y: rat): rat

requires Rational(x)

requires Rational(y)

ensures Rational(add(x,y)) // Comment -> postcondition not verified

ensures add(x, y) == x + y

{

var n1: int, m1: int :| m1 > 0 && x == (n1 as real) / (m1 as real);

var n2: int, m2: int :| m2 > 0 && y == (n2 as real) / (m2 as real);

//var r1 := x + y; // Uncomment -> postcondition not verified

var r: rat := ((n1 * m2 + n2 * m1) as real) / ((m1 * m2) as real);

assert Rational(r);

//assert r == x + y; // Uncomment -> much higher resource use

r

}This function will verify without too much difficulty using Dafny 3.13.1, but not at all with Dafny 4.x. Even with Dafny 3.13.1, verification is brittle. Removing ensures Rational(add(x, y)) leads to a failure to prove the other ensures clause, even though assert Rational(r) is a statement of the same fact. Adding var r1 := x + y also leads to the postcondition not being verified, even though r1 is never used (and even though assert r == x + y succeeds).

Measuring and reducing brittleness

Note that the last of these commented lines, assert r == x + y, hints at one of the concepts we’ll use to help reduce brittleness, because brittleness tends to be correlated to the difficulty of verification. Execution time is one way to measure difficulty, but execution time can vary widely, especially when doing verification on cloud-hosted computers. Another measure of difficulty, with greater reproducibility, is the Z3-specific resource count. If you verify the example add function in VS Code (with the Dafny extension installed), you can hover over the function signature line and see a popup that lists “Total resource usage” in units labeled RU (for “resource units”). This number gives you an indication of how much work it took the SMT solver to verify a particular definition. And we’ll see that reducing this number helps reduce brittleness. In general, we tend to aim for less than around 200K RU per definition. For the add function we’re considering, using Dafny 3.13, the reported RU is around 679K on my Intel-based Mac laptop.

Before getting into specifics for how to reduce resource use, let’s step back for a moment to discuss what makes automated proofs difficult. The process that an automated prover goes through to establish the validity of a particular statement can be thought of as searching through the space of possible proofs. Roughly speaking, the prover has a starting point (facts that it takes as true at the beginning, such as those in preconditions and assumptions) and an ending point (facts that it’s trying to prove, such as those in postconditions and assertions). To get from the starting point to the ending point, it can repeatedly take a step by applying any one of a set of possible rules. The number of facts available at the starting point is directly proportional to the number rules available to apply, and the prover’s job is to successfully choose the rule that will most quickly get it closer to the ending point. The best rule is difficult to predict, however, so the choice is sometimes (or frequently) arbitrary (though SMT solvers are effective in practice partly because they have useful heuristics for making these choices). This means that the most reliable ways to make the prover’s job easier are to 1) reduce the number of alternative steps available to choose from at any given point, and 2) reduce the total length of the sequence of steps that must be taken to get from the starting point to the ending point.

In terms of Dafny programs, these two techniques take the form of 1) abstracting key concepts into self-contained definitions and lemmas, and 2) introducing additional proof structure to reduce the distance between the assumptions and conclusions at any given point. Self-contained definitions can ideally be made opaque and revealed only when necessary. Additional proof structure can take the form of conditionals, application of lemmas, calc statements, or assert statements.

A first variation on add

To improve our add example, it’s easiest to start with approach (2). Consider the following modification.

ghost function add2(x: rat, y: rat): rat

requires Rational(x)

requires Rational(y)

// ensures Rational(add2(x,y)) // Uncomment -> higher resource use with 3.13, failure with 4.3

ensures add2(x, y) == x + y

{

var x1: int, x2: int :| x2 > 0 && x == (x1 as real) / (x2 as real);

var y1: int, y2: int :| y2 > 0 && y == (y1 as real) / (y2 as real);

var r: real := x + y;

var final_d: int := x2 * y2;

// var r1 := x + y; // Uncomment -> higher resource use with 3.13, failure with 4.3

assert (x1 as real) / (x2 as real) == ((x1 * y2) as real) / ((x2 * y2) as real);

assert r == (((x1 * y2) + (y1 * x2)) as real) / (final_d as real);

// assert Rational(r); // Uncomment -> higher resource use with 3.13, failure with 4.3

// assert r == x + y; // Uncomment -> higher resource use with 3.13, failure with 4.3

r

}In this example, we’ve added two assert statements that represent intermediate steps in the calculation equating add(x, y) (or r) with x + y. These are similar to the intermediate points you might write out if you were to prove the equivalence by hand, applying standard rules of algebra. We’ve also removed the Rational(add(x, y)) postcondition. We included it originally only because the first version wouldn’t verify without it (although one might want to prove it for its own sake). Because we don’t have that postcondition, we also don’t need assert Rational(r).

With these changes, it now verifies using about 637K RU, which is less, but not significantly less. However, in this case it’s enough to allow it to verify with Dafny 4.3.0, as well! The resource counts between different Z3 versions aren’t directly comparable, and Dafny changed its default Z3 version between 3.x and 4.x, so the resource counts between 3.13.1 and 4.3.0 aren’t directly comparable. However, for comparison with later examples, Dafny 4.3.0 reports 303K RU on add2 on my laptop.

Measuring brittleness more thoroughly

We can dig even more deeply into the difference between these two examples than we did above, however. The commented lines indicate that both small changes in the program and changes in Dafny version can cause failures, so this example is still quite brittle. To demonstrate this in practice, we can automatically check what happens when we verify with either different Dafny versions or different variants of the program. Automating the process of checking a given verification with multiple Dafny versions can be implemented in a CI script without much difficulty, and we won’t go into more detail about that here. To automate comparison of different variants of the program, Dafny includes a feature to perform a certain set of very simple random mutations to evaluate whether any of these mutations make verification more difficult or more prone to failure.

This feature is encapsulated in the dafny measure-complexity command. The most basic use takes the form:

dafny measure-complexity --iterations N file.dfyThis is roughly equivalent to dafny verify file.dfy, except that it attempts verification N times, with random changes applied during each attempt. The changes occur at the SMT level, rather than the Dafny source code level, and consist of reordering definitions and renaming variables, as well as passing a random seed on to the SMT solver for use in making the arbitrary decisions described earlier.

Running dafny measure-complexity --iterations 5 on the add2 function results in two failures, for me, one for each assertion, using Dafny 4.3.0. (We’ll be using Dafny 4.3.0 for the rest of this post but, just for comparison, Dafny 3.13.1 times out, with a 10s limit, on one out of those 5 iterations. Dafny 4.3.0 completes in less than 10s for each iteration, even when it fails.)

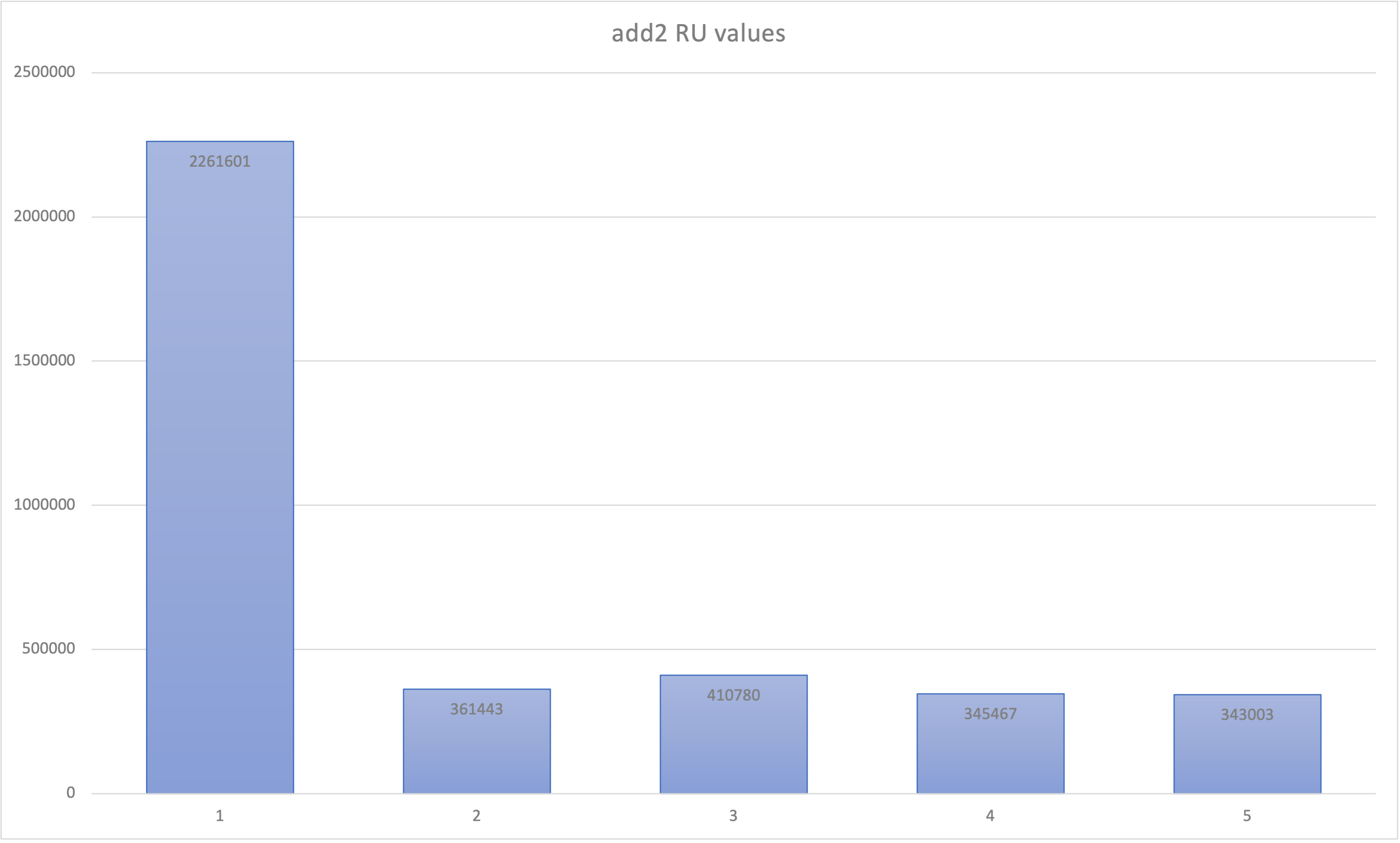

That simple invocation allows you to identify how often a verification fails, when running with multiple random mutations, but it’s possible to get more detail about each iteration. If you add the --log-format csv argument, Dafny will create a CSV file containing the outcome, running time, and resource count of each iteration of each definition. Running on the add2 example above, I get the following. (In this graph, each bar represents a separate iteration, and the height indicates the resource usage.)

In this experiment, iterations 1 and 3 failed verification, and the others succeeded. Note that the resource counts for the successful proofs are all in roughly the same range, but the resource counts for the failed iterations are larger (and in one case much larger). We find that even in cases where no iterations fail, large variations in resource counts between successful runs can be an early predictor of brittleness. So, although this example is improved from the first version, it clearly could use work to further reduce brittleness.

A second variation on add

The next step we’ll take is focused on reducing the number of possible reasoning steps available to the prover at any given point, and we’ll do this by breaking the problem up into smaller pieces, each of which is verified independently. We’ll do this by proving each of the facts specified in the first three assertions of add2 in separate lemmas. For each lemma, the prover has access to only the facts listed explicitly in requires clauses (as opposed to the results of previous assert statements, or requires clauses of the add3 function, for example).

lemma AddStep1(x1: int, x2: int, y1: int, y2: int)

requires x2 > 0

requires y2 > 0

ensures (x1 as real) / (x2 as real) == ((x1 * y2) as real) / ((x2 * y2) as real)

{}

lemma AddStep2(r: real, x:real, y: real, x1: int, x2: int, y1: int, y2: int)

requires x2 > 0

requires x == (x1 as real) / (x2 as real)

requires y2 > 0

requires y == (y1 as real) / (y2 as real)

requires r == x + y

ensures r == (((x1 * y2) + (y1 * x2)) as real) / ((x2 * y2) as real)

{}

lemma AddStep3(r: real, x:real, y: real, x1: int, x2: int, y1: int, y2: int)

requires x2 > 0

requires x == (x1 as real) / (x2 as real)

requires y2 > 0

requires y == (y1 as real) / (y2 as real)

requires r == x + y

requires (x1 as real) / (x2 as real) == ((x1 * y2) as real) / ((x2 * y2) as real)

requires r == (((x1 * y2) + (y1 * x2)) as real) / ((x2 * y2) as real)

ensures Rational(r)

{}

ghost function add3(x: rat, y: rat): rat

requires Rational(x)

requires Rational(y)

//ensures Rational(add3(x, y)) // Fine

ensures add3(x, y) == x + y

{

var x1: int, x2: int :| x2 > 0 && x == (x1 as real) / (x2 as real);

var y1: int, y2: int :| y2 > 0 && y == (y1 as real) / (y2 as real);

var r: real := x + y;

// var r1 := x + y; // Fine

AddStep1(x1,x2,y1,y2);

AddStep2(r,x,y,x1,x2,y1,y2);

AddStep3(r,x,y,x1,x2,y1,y2); // Higher resource use if left out, even without postcondition

// assert r == x + y; // Fine

r

}On this code, Dafny reports 243K RU for the add3 function. Note that it also spends some time proving each of the other definitions, so the total resource use is higher than for add2. However, for the purposes of brittleness, the resource use of any single goal is the key factor. Total resource use is less important.

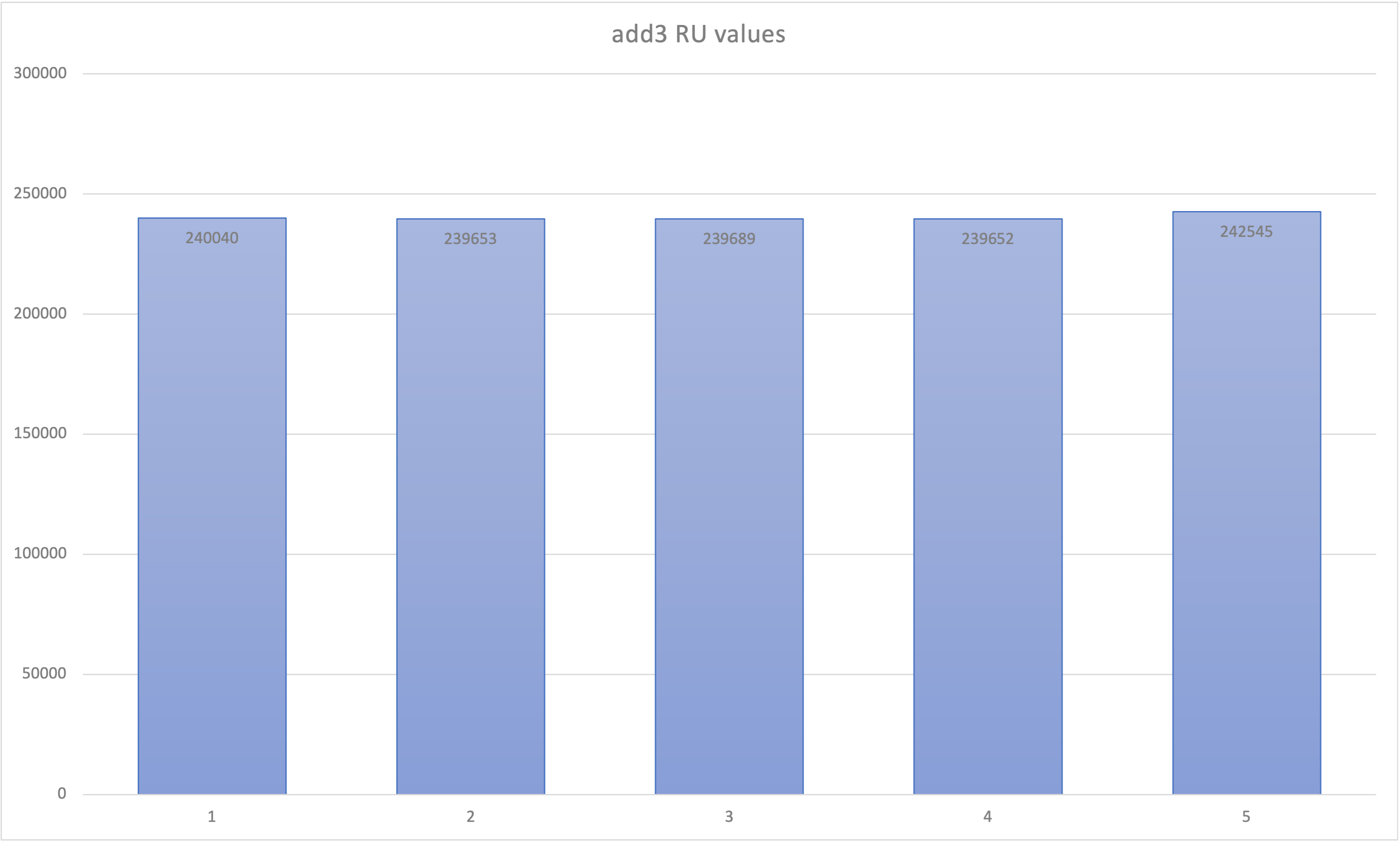

In addition to the reduced resource use, dafny measure-complexity --iterations 5 never fails. The output shows the following resource use for add3.

Note that the values for all iterations are quite close (which they also are for the accompanying lemmas). In addition, we can successfully verify add3 with Dafny 3.13.1, 4.0.0, 4.1.0, 4.2.0, 4.3.0, and likely other versions, as well.

More detailed structure

The rational addition example we’ve covered so far allows for two key improvements: adding inline assertions and extracting the proofs of those assertions to separate lemmas. However, other types of proof structure can be specified in Dafny, and these additional types of structure are often even more effective.

Consider the following module declaring a TriangleSum function and assuming some lemmas about its behavior (which happen to be sufficient to specify it precisely).

ghost function TriangleSum(n: nat): nat

lemma TriangleSumBase()

ensures TriangleSum(0) == 0

lemma TriangleSumRec()

ensures forall n: nat :: n > 0 ==> TriangleSum(n) == n + TriangleSum(n - 1)Based on these lemmas, we can prove that the result of TriangleSum is equivalent to a closed formula: (n * (n + 1)) / 2. This proof is naturally an inductive one, but Dafny doesn’t automatically know to apply induction because it doesn’t see a recursive function definition. So we need to do at least a little work to tell it to depend on a proof of the identity for n - 1 when proving the identity for any n bigger than zero. And we need to tell Dafny to use the two provided lemmas. Applying these two ideas leads to the following lemma.

lemma Proof1(n: nat)

ensures TriangleSum(n) == (n * (n + 1)) / 2

{

TriangleSumBase();

TriangleSumRec();

if n > 0 {

Proof1(n - 1);

}

}Dafny is able to prove this, but it takes over 1M RU to do so. This is partly because the postconditions from both lemmas are in scope everywhere, even though one is useful only for the base case and one is useful only for the inductive case. We can tell Dafny when to use each lemma by including a conditional statement.

lemma Proof2(n: nat)

ensures TriangleSum(n) == (n * (n + 1)) / 2

{

if n == 0 {

TriangleSumBase();

} else {

assert TriangleSum(n) == n + TriangleSum(n - 1) by {

TriangleSumRec();

}

Proof2(n - 1);

}

}When conditioning the proof on whether n is zero or not, we can invoke the base case lemma only when it is, and invoke the inductive case lemma only when it is not. In addition, we use assert by to specialize the result of TriangleSumRec to the specific instantiation we need for the proof. With these two additional bits of structure, the resource use goes down to around 100K.

Note that invoking the assumed lemmas about TriangleSum in the correct place is critical. If we use the same conditional structure but invoke both at the beginning, so they scope over the entire lemma, Dafny now uses over 1M RU again.

lemma Proof3(n: nat)

ensures TriangleSum(n) == (n * (n + 1)) / 2

{

TriangleSumBase();

TriangleSumRec();

if n == 0 {

} else {

assert TriangleSum(n) == n + TriangleSum(n - 1);

Proof3(n - 1);

}

}As an exercise, it can be instructive to try to make the resource use of this example even smaller. It's possible to get it below 70K!

More general guidelines

The examples covered so far illustrate two key principles for maintainable verification:

- Break long leaps of reasoning down into smaller steps. This limits the number of reasoning steps that the prover needs to construct on its own.

- Isolate each step so that the proof of it doesn’t need to (and, further, isn’t able to) take into account irrelevant information. This limits the number of choices that the prover has to evaluate when making each reasoning step.

A nice coincidence is that programs written according to these principles tend to be easier to read, as well. Reducing the work a prover needs to do when reasoning about a program has the effect of reducing the amount of thinking a human has to do to understand what a program does, and why it’s correct. Constructing small, relatively isolated components relates strongly to the concepts of cohesion and coupling used in software engineering.

Those principles are rather general, however, and there are several more specific guidelines for how to apply them in practice in Dafny.

- Prefer

opaquefunctions, with explicitrevealstatements where necessary. - Avoid

requiresandensuresclauses on functions (intrinsic specifications), except when necessary to make them total, and prefer a collection oflemmas, each of which establishes a single property of the function (extrinsic specifications). - Avoid lemmas that establish universally-qualified facts, preferring an additional parameter for each variable that would otherwise be quantified. It’s possible to wrap such a lemma to use universal quantification if it’s necessary, but many uses can pass in specific instantiations.

- Avoid subset types except perhaps for simple integer ranges.

- Prove the correctness of each method by including a single postcondition that establishes equivalence with a function or agreement with a relation. Other properties can be proved as independent lemmas about that function or relation.

The Dafny-VMC project includes some more detailed guidelines. Sometimes it can be difficult to re-architect large, existing systems to follow those guidelines strictly, and we have some additional documentation on optimizing verification that includes techniques that can help in this case.

Conclusion

Brittleness is an inevitable consequence of the combination of expressiveness and automation available in Dafny. However, although it is unavoidable in theory, it can be dramatically reduced in practice, and an important part of good verified software engineering is to continually improve the quality of the proofs. Aiming to reduce resource use, and setting limits on it as part of your build process, is one of the most effective ways to do so. This can be achieved by writing code in small, self-contained units that each have a clear, single purpose and don’t leak implementation details except when necessary. Within these units, additional details about intermediate proof steps can help. Although assert and calc statements are the most straightforward way to do this, using the structure of natural deduction can be even more effective.

When constructing new Dafny projects, we recommend using a project file something like the following.

[options]

resource-limit = 200

default-function-opacity = Opaque