How to use Dafny to prove type safety

There are many ways even well tested programs can go wrong (see my previous blog post on how Dafny helps).

Static typing often solves a class of these programming issues entirely by preventing unintended usage of a value.

There are many ways even well tested programs can go wrong (see my previous blog post on how Dafny helps).

Static typing often solves a class of these programming issues entirely by preventing unintended usage of a value.

This blog post takes a deep dive… take a deep breath… on how to write terms of a programming language, and both a type-checker and an evaluator on such terms, such that the following soundness property holds:

- [Progress] If a type checker accepts a term, then the evaluator will not get stuck on that term.

- [Preservation] If a term has a type T, then the evaluator will also return a term of type T

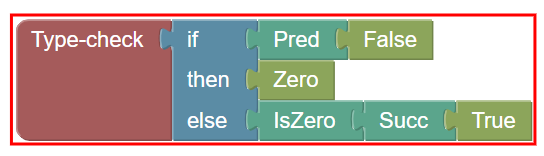

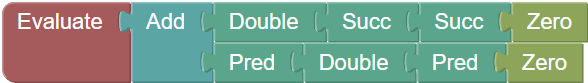

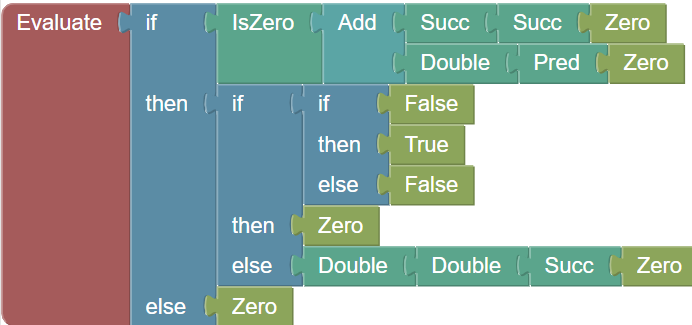

We will illustrate this using the infrastructure of the following Blockly workspace. If you build a full term and pass it to “Type check”, on success, the block is surrounded with green, otherwise with red. If surrounded with green, then attaching the term to “Evaluate” and clicking on “Evaluate” will always do something, except if the term is a final value. “Evaluate” is surrounded in red if its term does not type check.

Play with the evaluator and the type checker

By the way, have you seen that Pred(False) does not type check?

Someone made the remark that it’s counter-intuitive, because they thought that Pred would

stand up for Predicate and so it should type check. But Pred stands for Predecessor,

and that’s why it applies only to numbers. The type-checker’s role is also to solve such ambiguities before the execution.

Examples

Feel free to click on the examples below to load them in the Blockly workspace above.

Writing a type checker in Dafny

Writing a type-checker that guarantees that evaluation of a term won’t get stuck is not an easy task as we must dive into maths, but fortunately, Dafny makes it easier.

The term language

First, let’s define the term language used in the Blockly interface above. Note that the logic of the Blockly workspace above uses that exact code written on this page. Yeah, Dafny compiles to JavaScript too!

datatype Term =

| True

| False

| Zero

| Succ(e: Term)

| Pred(e: Term)

| IsZero(e: Term)

| Double(e: Term)

| Add(left: Term, right: Term)

| If(cond: Term, thn: Term, els: Term)

The type language

Let’s also add the two types our expressions can have.

datatype Type =

| Bool

| Int

The type checker

We can now write a type checker for the terms above. In our case, a type checker will take a term, and return a type if the term has that type. We will not dive into error reporting in this blog post.

First, because a term may or may not have a type, we want an Option<A> type like this:

datatype Option<A> = Some(value: A) | None

Now, we can define a function that computes the type of a term, if it has one. For example, in a conditional term, the condition has to be a boolean, while we only require the “then” and “else” part to have the same, defined type. In general, computing types is a task linear in the size of the code, whereas evaluating the code could have any complexity. This is why type checking is an efficient way of preventing obvious mistakes.

function GetType(term: Term): Option<Type> {

match term {

case True => Some(Bool)

case False => Some(Bool)

case Zero => Some(Int)

case Succ(e) =>

if GetType(e) == Some(Int) then

Some(Int)

else

None

case Pred(e) =>

if GetType(e) == Some(Int) then

Some(Int)

else

None

case IsZero(e) =>

if GetType(e) == Some(Int) then

Some(Bool)

else

None

case Add(left, right) =>

if GetType(left) == Some(Int) == GetType(right) then

Some(Int)

else

None

case Double(e) =>

if GetType(e) == Some(Int) then

Some(Int)

else

None

case If(cond, thn, els) =>

var t := GetType(thn);

var e := GetType(els);

if GetType(cond) == Some(Bool) && t == e then

t

else

None

}

}

A well-typed term is one for which a type exists.

predicate WellTyped(term: Term) {

GetType(term) != None

}

The evaluator and the progress check

At first, we can define the notion of evaluating a term. We can evaluate a term using small-step semantics, meaning we only replace a term or a subterm by another one. Not being stuck means that we will always be able to find a term to “replace” or to “compute”, it’s a bit of a synonym here.

There are terms where no replacement is possible: value terms. Here is what we want them to look like: either booleans, zero, positive integers, or negative integers.

predicate IsSuccs(term: Term) {

term == Zero || (term.Succ? && IsSuccs(term.e))

}

predicate IsPreds(term: Term) {

term == Zero || (term.Pred? && IsPreds(term.e))

}

predicate IsFinalValue(term: Term) {

term == True || term == False || term == Zero ||

IsSuccs(term) || IsPreds(term)

}

Now, we can write our one-step evaluation method. As a requirement, we add that the term must be well-typed and nonfinal.

function OneStepEvaluate(e: Term): (r: Term)

requires WellTyped(e) && !IsFinalValue(e)

{

match e {

case Succ(Pred(x)) =>

x

case Succ(succ) =>

Succ(OneStepEvaluate(succ))

case Pred(Succ(x)) =>

x

case Pred(pred) =>

Pred(OneStepEvaluate(pred))

case IsZero(Zero) =>

True

case IsZero(e) =>

if IsFinalValue(e) then

assert e.Pred? || e.Succ?;

False

else

IsZero(OneStepEvaluate(e))

case Add(a, b) =>

if !IsFinalValue(a) then

Add(OneStepEvaluate(a), b)

else if !IsFinalValue(b) then

Add(a, OneStepEvaluate(b))

else if a.Zero? then

b

else if b.Zero? then

a

else if a.Succ? then

Succ(Add(a.e, b))

else

assert a.Pred?;

Pred(Add(a.e, b))

case Double(a) =>

if IsFinalValue(a) then

Add(a, a)

else

Double(OneStepEvaluate(a))

case If(cond, thn, els) =>

if IsFinalValue(cond) then

assert GetType(cond) == Some(Bool);

assert cond == True || cond == False;

if cond == True then

thn

else

assert cond == False;

els

else

If(OneStepEvaluate(cond), thn, els)

}

}

The interesting points to note about the function above, in a language like Dafny where every pattern must be exhaustive, are the following:

- Every call consists either of

OneStepEvaluateon one sub-argument, or a transformation that reduces the size of the tree. So something is always happening here. - All the cases are covered, Dafny does not complain!

- For example, when encountering the case

IsZero(e), ifeis a final value, it must be eitherPredorSucc. It cannot beTrueorFalseas it’s well-typed and the previous pattern precludesZero. - Similarly, if the condition of an if term is a final value, because it’s well-typed, Dafny knows it’s either

TrueorFalse.

- For example, when encountering the case

That concludes the progress part of soundness checking: whenever a term type-checks, there is always an applicable small step evaluation rule unless it’s a final value.

The preservation check

Soundness has another aspect, preservation, as stated in the intro. It says that, when evaluating a well-typed term, the evaluator will not get stuck and the result will have the same type as the original term. Dafny can also prove it for our language, out of the box. Well done, that means our language and evaluator make sense together!

lemma OneStepEvaluateWellTyped(e: Term)

requires WellTyped(e) && !IsFinalValue(e)

ensures GetType(OneStepEvaluate(e)) == GetType(e)

{

// Amazing: Dafny can prove this soundness property automatically

}

Conclusion

All the code above powers this page, which is why I can guarantee you that you won’t be able to find a term that the type checker accepts and that won’t result in a final value. Of course, in a real programming language term, you might add some infinite loops, but the soundness property above is not about termination, it’s about constant progress, which you also want in embedded systems to ensure they never need reboot.

Now that you know what a type checker is and how to implement one in Dafny, perhaps you will feel much better prepared to model and experiment on your new programming language, like recently the Cedar team did?

This is the end of the blog post. I hope you enjoyed it!

Bonus: more advanced modeling

If you are looking for some advanced concepts, feel free to continue reading! Beware, math ahead!

Sometimes, modeling the evaluator and the type-checker as functions is not enough. One wants to model them as relations, and determine some properties about these relations, such as the order of evaluation being irrelevant for the final result.

In the rest of this blog post, largely inspired by the book “Types and Programming Languages”, Chapter 8, written by Benjamin Pierce, I will illustrate one element of the proof: the one that inductive and constructive versions of the set of terms are equivalent. Having equivalence enables obtaining other results out of the scope of this blog post, including that the order of evaluation does not matter.

With the help of this trick, it becomes possible to prove similar equivalences for different inductive and constructive definitions of:

- The set of

(Expr, Expr)of small-step evaluations - The set of

(Expr, Type)of type checking

but I leave these as an exercise for the interested reader.

In Types and Programming Languages, chapter 3.2, we discover that there are two other mathematical definitions of the “set of all terms”. The first one in definition 3.2.1 states that the set of terms is the smallest set \(𝒯\) such that:

- \(\{\texttt{true}, \texttt{false}, 0\} \subseteq 𝒯\);

- if \(t_1 \in 𝒯\), then \(\{\texttt{succ}\;t_1, \texttt{pred}\;t_1, \texttt{is_zero}\;t_1\} \subseteq 𝒯\);

- if \(t_1 \in 𝒯\), \(\;\; t_2 \in 𝒯\) and \(t_3 \in 𝒯\), then \(\texttt{if}\;t_1\;\texttt{then}\;t_2\;\texttt{else}\;t_3 \in 𝒯\).

Note that these terms omit Double and Add above. This means we cannot state that this set is the same as set t: Term | true as one would like to write, but let’s continue.

We can write the inductive definition above in Dafny too:

ghost const AllTermsInductively: iset<Term>

ghost predicate InductionCriteria(terms: iset<Term>) {

&& True in terms && False in terms && Zero in terms

&& (forall t1 <- terms :: Succ(t1) in terms)

&& (forall t1 <- terms :: Pred(t1) in terms)

&& (forall t1 <- terms :: IsZero(t1) in terms)

&& (forall t1 <- terms, t2 <- terms, t3 <- terms

:: If(t1, t2, t3) in terms)

}

lemma {:axiom} InductiveAxioms()

ensures InductionCriteria(AllTermsInductively)

ensures forall setOfTerms: iset<Term> | InductionCriteria(setOfTerms)

:: AllTermsInductively <= setOfTerms

The second definition for the set of all terms in section 3.2.3 is done constructively. We first define a set \(S_i\) for each natural number \(i\), as follows

\(S_0 = ∅\);

\(\begin{aligned}S_{i+1} = && && \{\texttt{true}, \texttt{false}, 0\} \\ && \bigcup && \{\texttt{succ}\;t_1, \texttt{pred}\;t_1, \texttt{is_zero}\;t_1 \mid t_1 \in S_i \} \\ && \bigcup && \{\texttt{if}\;t_1\;\texttt{then}\;t_2\;\texttt{else}\;t_3\mid t_1 \in S_i,\; t_2 \in S_i,\; t_3 \in S_i\}\end{aligned}\).

This we can enter in Dafny too:

ghost function S(i: nat): iset<Term> {

if i == 0 then

iset{}

else

iset{True, False, Zero}

+ (iset t1 <- S(i-1) :: Succ(t1))

+ (iset t1 <- S(i-1) :: Pred(t1))

+ (iset t1 <- S(i-1) :: IsZero(t1))

+ (iset t1 <- S(i-1), t2 <- S(i-1), t3 <- S(i-1) :: If(t1, t2, t3))

}

ghost const AllTermsConstructively: iset<Term> := iset i: nat, t <- S(i) :: t

But now, we are left with the existential question: are these two sets the same?

We rush in Dafny and write a lemma ensuring AllTermsConstructively == AllTermsInductively by invoking the lemma InductiveAxioms(), but… Dafny can’t prove it.

If you think deeply about it, how do you know that the two are the same? It seems obvious but why? It seems straightforward to prove that AllTermsInductively <= AllTermsConstructively because by definition, AllTermsConstructively obeys induction rules. But is it the smallest of such sets? But what if there was an element of AllTermsConstructively that is not in AllTermsInductively? It could actually happen if, instead of a datatype, we only had a trait, and some external user could implement new terms yet unknown to us.

Here is Benjamin Pierce’s proof sketch, then translated and verified in Dafny.

- First, prove

AllTermsInductively <= AllTermsConstructivelyby showing thatAllTermsConstructivelysatisfies the predicateInductionCriteria. - Second, for any set

somesetsatisfying the induction criteria, for everyi, we prove by induction that every set of termsS(i)is insidesomeset. AllTermsConstructivelybeing the union of all theseS(i), it is also contained in any set satisfying the induction criteria, includingAllTermsInductivelywhich is the smallest one, soAllTermsConstructively <= AllTermsInductively- From 1. and 3. we obtain

AllTermsConstructively == AllTermsInductively.

Let’s prove it in Dafny!

0. Intermediate sets are cumulative

First, we want to show that, for every i <= j, we have S(i) <= S(j) (set inclusion). We do this in two steps: first, we show this cumulative effect between two consecutive sets, and then

between any two sets.

We use the annotation {:vcs_split_on_every_assert} which makes Dafny verify each assertion independently, which, in this example, helps the verifier. Yes, helping the verifier is something we must occasionally do in Dafny.

To further control the situation, we use the annotation {:induction false} to ensure Dafny does not try to prove induction hypotheses by itself, which gives us control over the proof. Otherwise, Dafny can both automate the proof a lot (which is great!) and sometimes time out because automation is stuck (which is less great!). I left assertions in the code so that not only Dafny, but you too can understand the proof.

lemma {:vcs_split_on_every_assert} {:induction false} SiAreCumulative(i: nat)

ensures S(i) <= S(i+1)

{

forall t <- S(i) ensures t in S(i+1) {

match t {

case True | False | Zero => assert t in S(i+1);

case Pred(term) =>

assert term in S(i-1);

assert term in S(i) by {

SiAreCumulative(i-1);

}

assert t in S(i+1);

case Succ(term) =>

assert term in S(i-1);

assert term in S(i) by {

SiAreCumulative(i-1);

}

assert t in S(i+1);

case IsZero(term) =>

assert term in S(i-1);

assert term in S(i) by {

SiAreCumulative(i-1);

}

assert t in S(i+1);

case If(cond, thn, els) =>

assert cond in S(i-1) && thn in S(i-1) && els in S(i-1);

assert cond in S(i) && thn in S(i) && els in S(i) by {

SiAreCumulative(i-1);

}

assert t in S(i+1);

}

}

}

lemma SiAreIncreasing(i: nat, j: nat)

decreases j - i

requires i <= j

ensures S(i) <= S(j)

{

if i == j {

// Trivial

} else {

assert S(i) <= S(i+1) by {

SiAreCumulative(i);

}

assert S(i+1) <= S(j) by {

SiAreIncreasing(i + 1, j);

}

}

}

1. Smallest inductive set contained in constructive set

After proving that intermediate sets form an increasing sequence, we want to prove that the smallest inductive set is contained in the constructive set. Because the smallest inductive set is the intersection of all sets that satisfies the induction criteria, it suffices to prove that the constructive set satisfies the induction criteria.

Note that I use the annotation {:rlimit 4000} which is only a way for Dafny to say that every assertion batch should verify using less than 4 million resource units (unit provided by the underlying solver), which reduces the chances of proof variability during development.

lemma {:rlimit 4000} {:vcs_split_on_every_assert}

AllTermsConstructivelySatisfiesInductionCriteria()

ensures InductionCriteria(AllTermsConstructively)

ensures AllTermsInductively <= AllTermsConstructively

{

assert && True in AllTermsConstructively

&& False in AllTermsConstructively

&& Zero in AllTermsConstructively

by {

assert S(1) <= AllTermsConstructively;

}

forall t1 <- AllTermsConstructively

ensures && Succ(t1) in AllTermsConstructively

&& Pred(t1) in AllTermsConstructively

&& IsZero(t1) in AllTermsConstructively {

var i: nat :| t1 in S(i);

assert Succ(t1) in S(i+1);

assert Pred(t1) in S(i+1);

assert IsZero(t1) in S(i+1);

assert S(i+1) <= AllTermsConstructively;

}

forall t1 <- AllTermsConstructively,

t2 <- AllTermsConstructively,

t3 <- AllTermsConstructively

ensures If(t1, t2, t3) in AllTermsConstructively

{

var i :| t1 in S(i);

var j :| t2 in S(j);

var k :| t3 in S(k);

var max := if i <= j && k <= j then j else if i <= k then k else i;

SiAreIncreasing(i, max);

SiAreIncreasing(j, max);

SiAreIncreasing(k, max);

assert t1 in S(max) && t2 in S(max) && t3 in S(max);

assert If(t1, t2, t3) in S(max + 1);

}

InductiveAxioms();

}

2. Intermediate constructive sets are included in every set that satisfy the induction criteria

Now we want to prove that every S(i) is included in every set that satisfies the induction criteria. That way, their union, the constructive set, will also be included in any set that satisfies the induction criteria. The proof works by remarking that every element of S(i) is built from elements of S(i-1), so if these elements are in the set satisfying the induction criteria, so is the element by induction.

I intentionally detailed the proof so that you can understand it, but if you run it yourself, you might see that you can remove a lot of the proof and Dafny will still figure it out.

lemma {:induction false}

InductionCriteriaHasConcreteIAsSubset(

i: nat, someset: iset<Term>

)

requires InductionCriteria(someset)

ensures S(i) <= someset

{

if i == 0 {

// The empty set is always a subset of anything

} else {

InductionCriteriaHasConcreteIAsSubset(i-1, someset);

assert S(i-1) <= someset;

forall elem <- S(i) ensures elem in someset {

var bases := iset{True, False, Zero};

var succs := iset t1 <- S(i-1) :: Succ(t1);

var preds := iset t1 <- S(i-1) :: Pred(t1);

var iszeros := iset t1 <- S(i-1) :: IsZero(t1);

var ifs := iset t1 <- S(i-1), t2 <- S(i-1), t3 <- S(i-1) :: If(t1, t2, t3);

assert S(i) == bases + succs + preds + iszeros + ifs;

if elem in bases {

assert elem.True? || elem.False? || elem.Zero?;

assert elem in someset;

} else if elem in succs {

assert elem in someset by {

assert elem.Succ?;

assert elem.e in S(i-1);

assert elem.e in someset;

assert Succ(elem.e) in someset;

}

} else if elem in preds {

assert elem in someset by {

assert elem.Pred?;

assert elem.e in S(i-1);

assert elem.e in someset;

assert Pred(elem.e) in someset;

}

} else if elem in iszeros {

assert elem in someset by {

assert elem.IsZero?;

assert elem.e in S(i-1);

assert elem.e in someset;

assert IsZero(elem.e) in someset;

}

} else {

assert elem in ifs;

assert elem in someset by {

assert elem.cond in S(i-1) && elem.thn in S(i-1) && elem.els in S(i-1);

assert elem.cond in someset && elem.thn in someset && elem.els in someset;

assert If(elem.cond, elem.thn, elem.els) in someset;

}

}

}

}

}

3. The constructive set is included in the smallest inductive set that satisfies the induction criteria

We can deduce from the previous result that the constructive definition of all terms is also included in any set of term that satisfies the induction criteria. From this we can deduce automatically that the constructive definition of all terms is included in the smallest inductive set satisfying the induction criteria.

// 3.2.6.b.1 AllTermsConstructively is a subset of any set satisfying the induction criteria (hence AllTermsConstructively <= AllTermsInductively)

lemma AllTermsConstructivelyIncludedInSetsSatisfyingInductionCriteria(

terms: iset<Term>

)

requires InductionCriteria(terms)

ensures AllTermsConstructively <= terms

{

forall i: nat ensures S(i) <= terms {

InductionCriteriaHasConcreteIAsSubset(i, terms);

}

}

lemma AllTermsConstructivelyIncludedInAllTermsInductively()

ensures AllTermsConstructively <= AllTermsInductively

{

InductiveAxioms();

AllTermsConstructivelyIncludedInSetsSatisfyingInductionCriteria(AllTermsInductively);

}

4. Conclusion with the equality

Because we have <= and >= between these two sets, we can now prove equality.

lemma InductionAndConcreteAreTheSame()

ensures AllTermsConstructively == AllTermsInductively

{

InductiveAxioms();

AllTermsConstructivelySatisfiesInductionCriteria();

AllTermsConstructivelyIncludedInAllTermsInductively();

}

Bonus Conclusion

We were able to put together two definitions for infinite sets, and prove that these sets were equivalent. As stated in the introduction, having multiple definitions of a single infinite set makes it possible to pick the definition adequate to the job to prove other results. For example,

- If a term is in the constructive set, then it cannot be constructed with

Addfor example, because it would need to be in aS(i)and none of theS(i)defineAdd. This can be illustrated in Dafny with the following lemma:

lemma {:induction false} CannotBeAdd(t: Term)

requires t in AllTermsConstructively

ensures !t.Add?

{

// InductiveAxioms(); // Uncomment if you use AllTermsInductively

}

which Dafny can verify pretty easily. However, if you put AllTermsInductively instead of AllTermsConstructively, Dafny would have a hard time figuring out.

- If

xis in the inductive set, thenSucc(x)is in the inductive set as well. Dafny can figure it out by itself using theAllTermsInductivelydefinition, but won’t be able to do it withAllTermsConstructivelywithout a rigorous proof.

lemma {:induction false} SuccIsInInductiveSet(t: Term)

requires t in AllTermsInductively

ensures Succ(t) in AllTermsInductively

{

InductiveAxioms();

}

This could be useful for a rewriter or an optimizer to ensure the elements it writes are in the same set.

Everything said, everything above can be a bit overweight for regular Dafny users. In practice, you’re better off writing the inductive predicate explicitly as a function rather than an infinite set with a predicate, so that you get both inductive and constructive axioms that enable you to prove something similar to the two results above.

predicate IsAdmissible(t: Term) {

match t {

case True => true

case False => true

case Zero => true

case Succ(v) => IsAdmissible(v)

case Pred(v) => IsAdmissible(v)

case IsZero(v) => IsAdmissible(v)

case If(c, t, e) => IsAdmissible(c) && IsAdmissible(t) && IsAdmissible(e)

case _ => false

}

}

lemma {:induction false} CannotBeAdd2(t: Term)

requires IsAdmissible(t)

ensures !t.Add?

{

}

lemma {:induction false} SuccIsInInductiveSet2(t: Term)

requires IsAdmissible(t)

ensures IsAdmissible(Succ(t))

{

}

This above example illustrates what Dafny does best: it automates all the hard work under the hood

so that you can focus on what is most interesting to you, and even better, it ensures you don’t need to define {:axiom} yourself in this case.

I hope you give Dafny a try and looking forward to your interesting questions!