Making Verification Compelling: Visual Verification Feedback for Dafny

If, one day, one of your developers introduced a bug that ends up costing your company millions, as it happens occasionally, what would be your first thought, as the manager? Probably

Now you’ll start hoping this will not happen, and you have good reasons to think so:

- “We have regression tests, integrations test, unit tests, alpha and beta testers.”

- “We have code coverage and we are at 100% … Well, almost, every uncovered line is documented.”

- “We have the best talent here, they hopefully won’t fail.”

And then, a dreaded thought reappears: “Well, despite all these efforts, how can I be sure that this won’t happen?”. You remember your other efforts:

- “We did try to make a model out of our algorithms and prove properties, but, well only that senior mathematician on another specialized team can understand and maintain it, and they are retiring soon…”

- “My developers have tried using modeling tools themselves but it’s like… manipulating mathematics is discouraging…”

If only doing mathematics at the software level was engaging and compelling… and then you remember Dafny and its new features you will have read about in this blog post.

What?

I’ll explain how mathematical reasoning of programs can be made more engaging by increasing the amount of negative, contextual and especially positive feedback in Dafny. The success was to the point where a user spontaneously said:

After asking them if we could quote that sentence, another user added “If he won’t, I say it for you to use”. A third one said:

Isn’t that a super cute testimony?

Dafny

Quick story of Dafny

Dafny started as an imperative programming language with built-in support for verification in 2008, but you probably haven’t heard a lot about it in the news. That’s because it’s in a special niche: It’s meant for programmers, but designed with verification as the first goal in mind.

Dafny has been successfully used in several industrial and academic settings. With its Java-like syntax and good type inference, Dafny has over 2k stars on GitHub. Dafny is being used both in academic circles to teach formal reasoning, as well as in industrial projects like IronFleet and IronClad projects, as part of the AWS Encryption SDK and as the model for the Amazon Verified Permissions.

Under the hood, Dafny reasons about programs, and can not only prove the absence of run-time exceptions, but also invariants and specific properties relating inputs and outputs.

A quick introduction to Dafny

By now, you might want to know what it means to reason about programs mathematically to avoid bugs that tests might not cover. It’s your lucky day, I made an animation to explain the process. Here is an example of an unoptimized program that computes the Euclidian division in Dafny. The Euclidian is the regular division you learned at school, and the result are the quotient and the remainder.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

method EuclidianDiv(a: int, b: int) returns (q: int, r: int) {

if a <= b {

q := 0;

r := a;

} else {

var q', r' := EuclidianDiv(a - b, b);

q := q' + 1;

r := r';

}

}

method Main() {

var a, b := 47, 13;

var q, r := EuclidianDiv(a, b);

print a, " = ", q, "*", b, " + ", r;

}

dafny run --no-verify euclidian.dfy, you get the following output:

Dafny program verifier did not attempt verification 47 = 3*13 + 8

If you were to run code coverage, you'd have 100% with your function. However, bugs can lurk in many more places... let's remove the --no-verify option. Click .

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

method EuclidianDiv(a: int, b: int) returns (q: int, r: int) {

if a <= b {

q := 0;

r := a;

} else {

var q', r' := EuclidianDiv(a - b, b);

q := q' + 1;

r := r';

}

}

method Main() {

var a, b := 47, 13;

var q, r := EuclidianDiv(a, b);

print a, " = ", q, "*", b, " + ", r;

}

--no-verify option (and add --show-snippets so that it gives a prettier output).

dafny run --show-snippets euclidian.dfy, you now get the following output:

euclidian.dfy(6,30): Error: cannot prove termination; try supplying a decreases clause

|

6 | var q', r' := EuclidianDiv(a - b, b);

| ^

euclidian.dfy(6,30): Error: decreases expression at index 0 must be bounded below by 0

|

6 | var q', r' := EuclidianDiv(a - b, b);

| ^

euclidian.dfy(1,20): Related location

|

1 | method EuclidianDiv(a: int, b: int) returns (q: int, r: int) {

| ^

Dafny program verifier finished with 1 verified, 2 errors

Dafny could not prove that the method terminates. Wait a second, does it? You think for a second, reasons like "Well, 'a' decreases, and once it's smaller than 'b', it terminates. And 'a' is always greater or equal to zero, but how do we tell Dafny? Let's revisit the code. Click .

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

method EuclidianDiv(a: int, b: int) returns (q: int, r: int)

requires 0 <= a && b != 0 // Just added

decreases a // Just added

{

if a <= b {

q := 0;

r := a;

} else {

var q', r' := EuclidianDiv(a - b, b);

q := q' + 1;

r := r';

}

}

method Main() {

var a, b := 47, 13;

var q, r := EuclidianDiv(a, b);

print a, " = ", q, "*", b, " + ", r;

}

requires clause to your method to ensure that

EuclidianDiv is not called with a negative a.

and also that b is not zero.

You also add a decreases a clause, and Dafny verifies that the expression a decreases when calling itself recursively, and is greater or equal to zero.

Clauses are checked statically by Dafny but not compiled nor executed, like a clever

type check, which is pretty nice.

dafny run --show-snippets euclidian.dfy, you get the following output:

euclidian.dfy(9,30): Error: decreases clause might not decrease | 9 | var q', r' := EuclidianDiv(a - b, b); | ^ Dafny program verifier finished with 1 verified, 1 error

Well, it seems that Dafny does not believe that a - b is less than a. Time for an assertion.

Assertions are like clauses, they are not compiled nor executed, Dafny will just check them during verification. Click .

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

method EuclidianDiv(a: int, b: int) returns (q: int, r: int)

requires 0 <= a && b != 0

decreases a

{

if a <= b {

q := 0;

r := a;

} else {

assert a - b < a; // Just added

var q', r' := EuclidianDiv(a - b, b);

q := q' + 1;

r := r';

}

}

method Main() {

var a, b := 47, 13;

var q, r := EuclidianDiv(a, b);

print a, " = ", q, "*", b, " + ", r;

}

dafny run --show-snippets euclidian.dfy, you get the following output:

euclidian.dfy(9,4): Error: assertion might not hold | 9 | assert a - b < a; // Just added | ^^^^^^ Dafny program verifier finished with 1 verified, 1 error

You start to realize that something is wrong. In your head, you see that "a - b < a" is the same as "-b < 0", which is the same as "b > 0". Surprise! You just found out that, if you accidentally called the function with a negative 'b', the function would loop forever! Click to correct that.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

method EuclidianDiv(a: int, b: int) returns (q: int, r: int)

requires 0 <= a && 0 < b // Just modified to use '<' instead of '!='

decreases a

{

if a <= b {

q := 0;

r := a;

} else {

assert a - b < a;

var q', r' := EuclidianDiv(a - b, b);

q := q' + 1;

r := r';

}

}

method Main() {

var a, b := 47, 13;

var q, r := EuclidianDiv(a, b);

print a, " = ", q, "*", b, " + ", r;

}

requires clause to your method to ensure that

EuclidianDiv is not called with a negative b

dafny run --show-snippets euclidian.dfy, you finally get it working:

Dafny program verifier finished with 2 verified, 0 errors 47 = 3*13 + 8

By turning on verification, you were able to fix a bug that your test coverage would not have spotted.

But Dafny does not stop here. Can you prove that you did the right thing, which is computing the quotient and remainder?

Let's figure out. We can add one ensures clause to verify a relationship between inputs and outputs. Click to proceed.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

method EuclidianDiv(a: int, b: int) returns (q: int, r: int)

requires 0 <= a && 0 < b

decreases a

ensures a == b * q + r // Just added

ensures 0 <= r < b // Just added

{

if a <= b {

q := 0;

r := a;

} else {

assert a - b < a;

var q', r' := EuclidianDiv(a - b, b);

q := q' + 1;

r := r';

}

}

method Main() {

var a, b := 47, 13;

var q, r := EuclidianDiv(a, b);

print a, " = ", q, "*", b, " + ", r;

}

ensures clause to your method to ensure that

EuclidianDiv actually returns what it is supposed to compute,

given some properties you know of Euclidian division.

Note that Dafny lets you write chaining comparisons. How many languages allow that?

dafny run --show-snippets euclidian.dfy, you get the following result:

euclidian.dfy(6,0): Error: a postcondition could not be proved on this return path No Dafny location information, so snippet can't be generated. euclidian.dfy(5,17): Related location: this is the postcondition that could not be proved | 5 | ensures 0 <= r < b // Just added | ^ Dafny program verifier finished with 1 verified, 1 error

From this, you see that Dafny was not able to prove that r < b always hold.

To identify why it is the case, you could apply techniques of verification debugging. For now, you just realize your mistake:

It's only if a < b that you should take the a = b, you should

take one more step recursively. Click to fix the code.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

method EuclidianDiv(a: int, b: int) returns (q: int, r: int)

requires 0 <= a && 0 < b

decreases a

ensures a == b * q + r

ensures 0 <= r < b

{

if a < b { // Fixed. Was previously 'a <= b'

q := 0;

r := a;

} else {

assert a - b < a;

var q', r' := EuclidianDiv(a - b, b);

q := q' + 1;

r := r';

}

}

method Main() {

var a, b := 47, 13;

var q, r := EuclidianDiv(a, b);

print a, " = ", q, "*", b, " + ", r;

}

a < b.

dafny run euclidian.dfy, you get the following result:

Dafny program verifier finished with 2 verified, 0 errors 47 = 3*13 + 8

Well done. You not only got it working, but you also proved that your implementation satisfies a high-level specification.

If you want to know how Dafny translates these programs into mathematical formulas, have a look at this discussion.

Ok, so now you know how Dafny works if it was run on the command line. For now, let’s focus on the most interesting part that changed since the last year: the Dafny IDE for VS Code.

Users feel the lack of feedback on the IDE

I regularly meet Dafny users, and sometimes ex-Dafny users, and I realize that they all had a hard time using Dafny. Not the language itself, but the verification experience part. Let’s say it, the IDE interface was not very friendly for many aspects. As it replicated the command line, until mid-2022, the IDE of choice for Dafny, VSCode, was doing for verification nothing more than running the command line and displaying verification error annotations in context.

Users frequently had questions such as:

- Are verification diagnostics obsolete? If a file verified in 30 seconds, it meant users had to wait all this time before getting feedback about the line they were working on. Diagnostics used to be published only once, after Dafny checked everything. Imagine the frustration of waiting 30 seconds to know if what you wrote made sense for Dafny, 50 times per day…

- Is Dafny actually stuck? Not long ago, the Dafny extension had numerous problems requiring frequent restarts, so it was even more frustrating. Users were ditching the “verification on change” mode and used “verification on save” to minimize the number of restarts, which impacted their experience a lot. The biggest problem was, there was no way to differentiate between “Dafny is stuck” and “Dafny is thinking”.

- Can we not verify a single method at a time?

In order to get feedback faster, users often commented out code, adding

{:verify false}orassume false;statements in the code to force Dafny to ignore already proved code. When they wanted to verify a single method, I’ve seen users go back to the command line (sigh). - Where are the hidden assertions? What are they proving? Dafny proves a ton of assertions that were never explicitly asserted by the user, such as preconditions, divisions by zero, or memory reading/writing conditions. If the program was verified, the users would usually have no idea of how much complex verification was performed, which did not provide as much assurance as if users knew all the work Dafny did.

- Is there no error on this assertion because it’s verified, or because Dafny has no information about it? Dafny made it clear where it found errors, but the absence of errors in some portions of a method could be due to Dafny not investigating further, because it had a default limit of 5 errors reported per method. So basically, it was impossible to know things about assertions that are not underlined in red as errors.

- Are there still assertions to prove in my current method? Professional programmers often wrote methods longer than could be displayed on the screen at once. Because postconditions are written at the beginning of a method, such users often needed to scroll back up to see if they finally proved it. Having no contextual information about the entire method verification status was painful.

So many questions that would block not only novice Dafny users, but also expert ones. Using Dafny myself, and supported by the entire Dafny team, I felt the strong need to do something about it.

Gutter-icon-based verification feedback

Gutter icons brought the first solution in that they offered easy-to-read and enhanced contextual feedback. You might remember the animated screenshot of our previous blog post:

I’m now going to explain in detail what is happening on the left of the code (the gutter), and how I designed it and especially how it answered many of the questions users were asking, sometimes unconsciously.

Numerous test engines also display feedback in the gutter next to the methods themselves, or next to the method calls if they are tests (e.g. Wallaby.js, xUnit…). Such feedback is contextual, meaning it can be associated to the line of code it is attached to, as opposed to diagnostics that are listed in a separate window. Because unit tests are much less common than pre- and postconditions in Dafny, and because I had the possibility to customize the icon for every line, I wondered: how can I leverage the gutter area to display verification feedback instead of usual test feedback?

While thinking about how to display verification feedback in the gutter, I established some principles that guided us during the design of both the icons and the user experience:

- Verified is visible but the least distracting: The icons for verified code should provide a simple positive feedback.

- Accessibility: The icons should not just have colors, but also easily recognizable shapes, so that color-blind people could still benefit from them.

- Compatibility with themes: The icon colors should be adequate both in light and dark mode.

- Compatibility with modes: The icons should work both if the user triggers verification on save, or if verification is triggered each time users type something

- Context-awareness: The icons should not just convey the verification status of a single line, but, where appropriate, they may also convey verification feedback about the surrounding context.

- Past-awareness: Icons indicating ongoing computation should still display previous verification status, so that it is not lost.

- Clarity: The icons should be simple, straightforward, and unambiguous even in users’ peripheral vision, so that users can focus on their code.

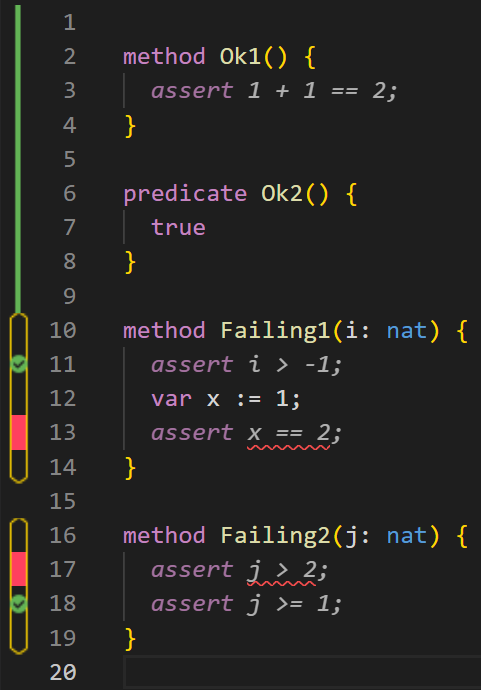

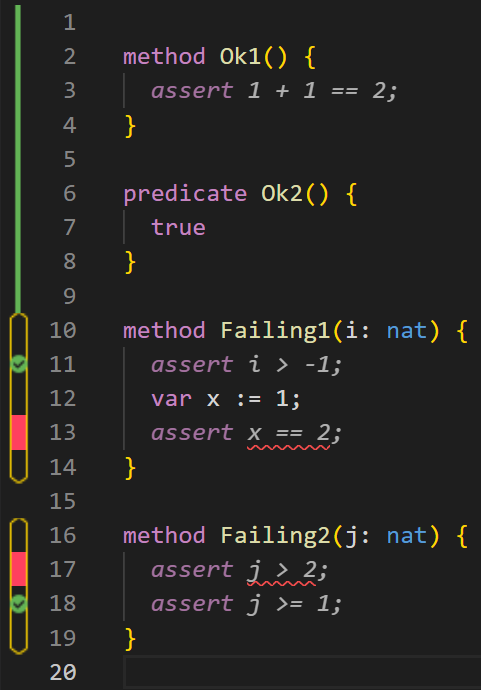

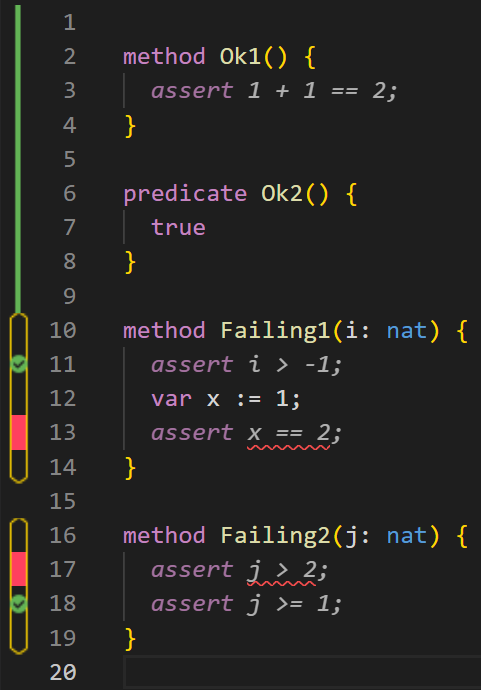

See below these icons in the current version of Dafny, on Visual Studio Code, when other gutter icon features are disabled.

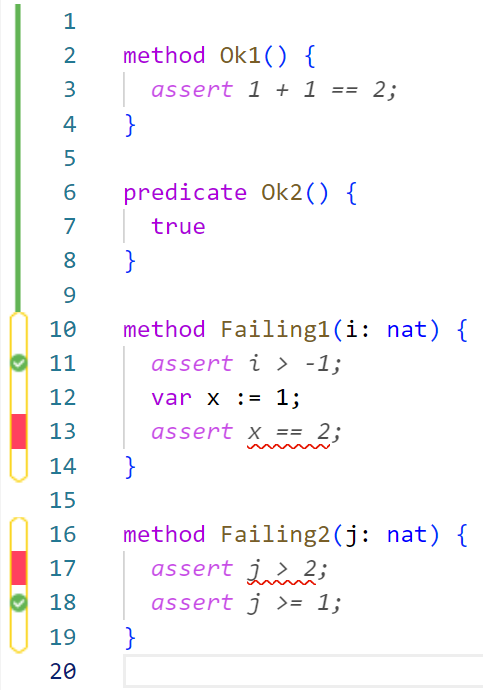

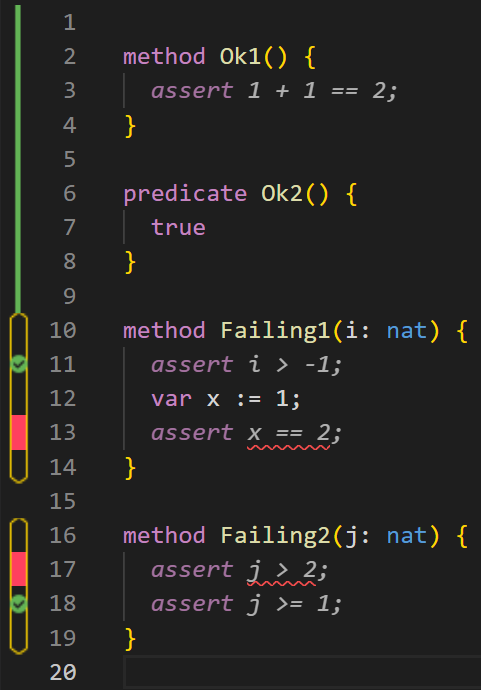

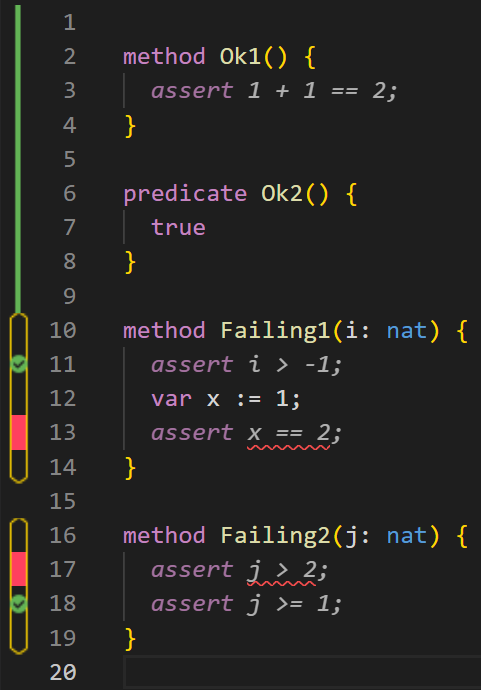

Figure 1 illustrates these icons in the current version of Dafny, on Visual Studio Code, when the other gutter icon features are disabled. I will now explain the design of these icons with respect to the principles above. I will then cover the dynamics of these icons and further visual feedback that provide an experience I wish to be delightful.

In the following, a declaration broadly consists of a block of code that Dafny can verify. Figure 1 presents 4 declarations: line 2 to 4, line 6 to 8, line 10 to 14, and line 16 to 19. In general, a declaration can be a method or a function with or without a body, a datatype definition, a constant declaration with or without a definition, or a subset type definition.

The verification icon set

Static icons

The first four icons that Dafny displays in the gutter are illustrated in Figure 1:

-

A green thin vertical bar for verified code. Figure 1, lines 1 to 9. Green was the obvious color of choice for verified code.

However, it was not obvious how to represent the notion of “verified”. In test frameworks, there is usually a check in front of passing tests.

In Dafny, the equivalent of a test is the verification of an entire declaration. Therefore, I decided to have an icon that could help form a vertical gap-free line through the declaration. Because eyes are sensitive to pattern breaks, I also decided to fill empty lines adjacent to green vertical icons (lines 1, 5, 9) also with the same green vertical icons. That way, verified code is the least distracting of all, brings a sense of relief when an entire error context goes away (see next points), and it conveys the idea that the default, or the goal, is to have verified icons.

However, it was not obvious how to represent the notion of “verified”. In test frameworks, there is usually a check in front of passing tests.

In Dafny, the equivalent of a test is the verification of an entire declaration. Therefore, I decided to have an icon that could help form a vertical gap-free line through the declaration. Because eyes are sensitive to pattern breaks, I also decided to fill empty lines adjacent to green vertical icons (lines 1, 5, 9) also with the same green vertical icons. That way, verified code is the least distracting of all, brings a sense of relief when an entire error context goes away (see next points), and it conveys the idea that the default, or the goal, is to have verified icons. -

A red rectangle for errors. Figure 1, line 13 and line 17. Red is the typical color for errors, so I used it for verification errors.

Similar to the choice of green, I used a less saturated red to avoid being too bright. The rectangle was one way to provide a prominent indication that there is at least one error on the line. The width of this rectangle is greater than the width of the verified icon, because it has to catch the eye when scrolling. If you look at it closely, you will also see that it is surrounded by two thin yellow lines (see the next point).

Similar to the choice of green, I used a less saturated red to avoid being too bright. The rectangle was one way to provide a prominent indication that there is at least one error on the line. The width of this rectangle is greater than the width of the verified icon, because it has to catch the eye when scrolling. If you look at it closely, you will also see that it is surrounded by two thin yellow lines (see the next point). -

Two vertical yellow lines for error context. Figure 1, lines 10-14 and 16-19. I wanted users to immediately recognize declarations that have errors.

That way, even if declarations span more than one screen and there are no more single-line errors on the screen, users would still know that work needs to be done in the surrounding declaration. I chose the color yellow for that, as it is the typical color for warnings. For the choice of shape, I used the clogged pipe metaphor, as if the context was a pipe in which errors were preventing the flow. This is how I ended up using two vertical yellow lines that were separated by the same width as the red rectangle.

That way, even if declarations span more than one screen and there are no more single-line errors on the screen, users would still know that work needs to be done in the surrounding declaration. I chose the color yellow for that, as it is the typical color for warnings. For the choice of shape, I used the clogged pipe metaphor, as if the context was a pipe in which errors were preventing the flow. This is how I ended up using two vertical yellow lines that were separated by the same width as the red rectangle. -

A circle with a check mark for partially proved assertions. Figure 1, line 11 and line 18. While designing the icons, we got access to not only errors and declarations,

but also to all the individual assertions. When Dafny finds an assertion it cannot prove, it will report it, assume it, and relaunch the verification process, up to five times per declaration. Therefore if, before the fifth time, it was able to prove that a declaration is correct, it means that every assertion not tagged with an error is partially proved.

This is especially useful in the context of verification debugging, when one tries to copy and rewrite assertions towards the top of the declaration, manually applying the weakest precondition calculus.

As expected, it solved the issue of users wondering if Dafny stopped at the first error or was able to prove the remaining. I also decided to not create an equivalent of this icon in a verified context, to keep the fully verified feedback as simple as possible.

but also to all the individual assertions. When Dafny finds an assertion it cannot prove, it will report it, assume it, and relaunch the verification process, up to five times per declaration. Therefore if, before the fifth time, it was able to prove that a declaration is correct, it means that every assertion not tagged with an error is partially proved.

This is especially useful in the context of verification debugging, when one tries to copy and rewrite assertions towards the top of the declaration, manually applying the weakest precondition calculus.

As expected, it solved the issue of users wondering if Dafny stopped at the first error or was able to prove the remaining. I also decided to not create an equivalent of this icon in a verified context, to keep the fully verified feedback as simple as possible.

Dynamic icons

Having icons for describing the verification status statically is great, but I found a clear benefit of using dynamic icons when displaying feedback. Typically, after looking at the verification diagnostics, users write more code or specifications, and then wait for verification to happen again. Verification can sometimes take dozens of seconds for a single file, so waiting for the entire verification of a file before updating icons would definitely not provide a good user experience…

I could just have removed verification icons while Dafny is verifying declarations. You can thank me, I did not chose this easy path, because I think that this would cause not only a disturbing blinking effect when verification is fast, but also make the user not benefit from immediate comparison with the previous status. In the weakest precondition calculus, I found it is helpful to see the red rectangle to “move up”, as it often means that someone is bringing an error closer to the hypotheses. Erasing the intermediate feedback would put more strain on vision processing because users would have to visually re-align the icons and the (usually indented) code.

I identified three dynamic phases for Dafny to provide feedback about its verification status. To stay true to the past-awareness principle, I slightly modified the static icons presented in the section about static icons to convey the notion of Dafny “working on verification” while still displaying previous icons. I present how these phases play together in Figure 2.

- The “verifying” phase. In this phase, illustrated in screenshots C, F and G, the icons resemble the static icons, except that they are traversed by an animated zig-zag line that indicates that Dafny is working on that code portion, but the previous results are still visible.

- The “obsolete” or “stale” phase. This phase uses static and dimmed versions of the icons in the “verifying” phase. This phase is visible in screenshots A and E of Figure 2, Dafny recognizes that something is new or has changed and that it is simply parsing and resolving the new code, but hasn’t started verification yet.

- The “unresolved” phase. This phase uses gray scale versions of the “obsolete” icons, except for parsing and resolution errors which are indicated by red triangles containing an exclamation point, like D of Figure 2.

I had to solve many challenges to ensure these icons provide the most adequate feedback. For example, as soon as some input is entered, before parsing even occurs, Dafny already migrates those icons according to string edits. I also found the lightning metaphor to be adequate to provide the sense of “verification” on the side of the vision field without hiding the previous verification status. However, I observed that if we just took the rectangle for error and put a lightning on it (yellow or transparent), it became hard-to-see in peripheral vision. This is especially important given that I had modified Dafny to give per-method feedback. This is why the red rectangle is split in screenshots E and F of Figure 2, as if the error was about to “go away”.

Among all the dynamic icons, note that lines 1 to 8 of Figure 2 is less distinct than for code in error context. Without more information about the new code, I preferred the dynamic icons to reflect a kind of default hypothesis that previously verified code will probably also be verified. I wanted Dafny to feel more helpful than inquisitive, i.e. optimistic about the ability for the user to write correct code.

I found it was appropriate to refresh these icons every time a declaration changes its verification status, in real-time. Moreover, in the current absence of a reliable caching mechanism, I added an edit detection mechanism to ensure that the last methods being edited are verified first. In Figure 2, verification being done on more than 2 cores, it was possible for the verification of the lines 1-7 to finish before the others.

Implementation details and cosmetics

To render static and dynamic icons, I used a z-buffer mechanism with clever codes for each icons.

I also have had special icons designed for the start and end of declarations with errors so that if flows nicely with verified code (for example  )

In real-time feedback, I also delayed the display of gutter icons by 2 seconds in the presence of parse or resolution errors, to avoid icons blinking when typing fast.

Finally, I ensured that the scroll bar itself reflects gutter icons, so that it’s possible to see at a glance if the entire file is verified, and if not, where to scroll.

)

In real-time feedback, I also delayed the display of gutter icons by 2 seconds in the presence of parse or resolution errors, to avoid icons blinking when typing fast.

Finally, I ensured that the scroll bar itself reflects gutter icons, so that it’s possible to see at a glance if the entire file is verified, and if not, where to scroll.

Enhanced positive and negative hover feedback

Congratulations on reading until here! So far, you already have a sense of how the interface of Dafny is almost gamified with its immersive UI experience, which contributes to making it delightful.

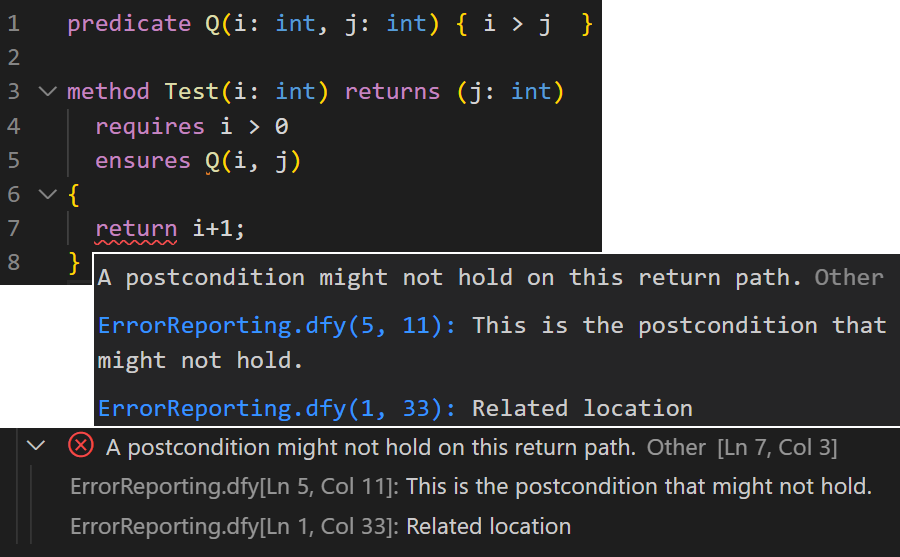

The gutter icons enhanced the user experience, but this was not enough. I found that I could further enhance the existing hover messages to provide useful insights and shortcuts. Let’s compare before/after:

{:vcs_split_on_every_assert}

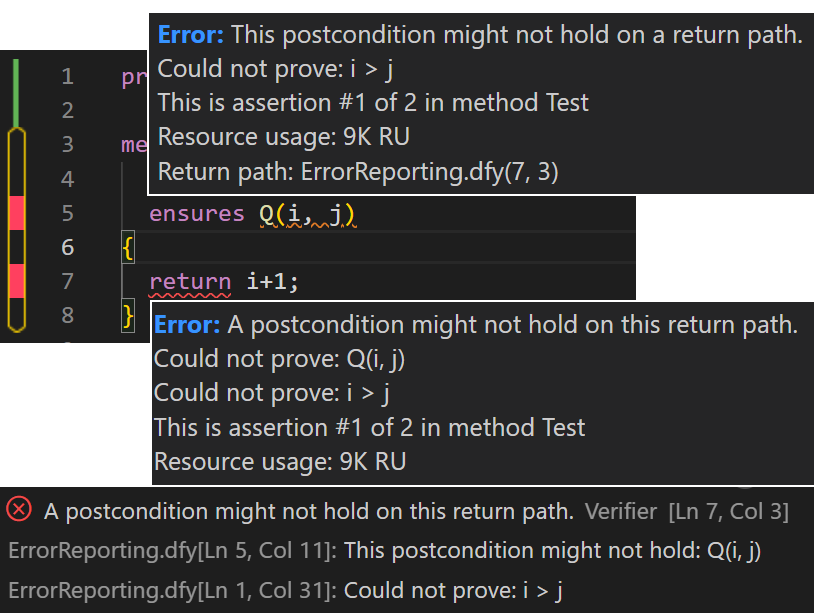

One aspect of program verification is that a single error might cover two or more places in the code. For example, post-conditions are asserted at every exit point of a declaration. Therefore, if this assertion fails, it fails on an exit point, and for the particular post-condition. Figure 3a shows that the error was never reported on the post-condition itself before (top image). Following user feedback, on Figure 3b I made the error visible on post-conditions, using a red-orange squiggly line in-code — to indicate it is a secondary error — and using the regular error icon in the gutter. Moreover, because hovering is one of first way users can discover features, I added the following improvements to the hover experience, as shown in the bottom of Figure 3b:

- We quote the exact code portions that Dafny could not prove.

- On the Error keyword, the usual color for links, I added a link to documentation we also wrote about how to fix failing assertions.

- “This is assertion #1 of 2” explains how many assertions there are and where is this assertion roughly located in verification, which proved to be useful for splitting verification in smaller tasks using annotations.

- “Resource usage: 9K RU” provides a metric on how many resource units (RU) the solver used to reach this verification result, which is more deterministic than elapsed verification time.

- Hovering over a proved assertion reveals similar insights, with a positive message instead of an error, such as “Success: The division is never zero”.

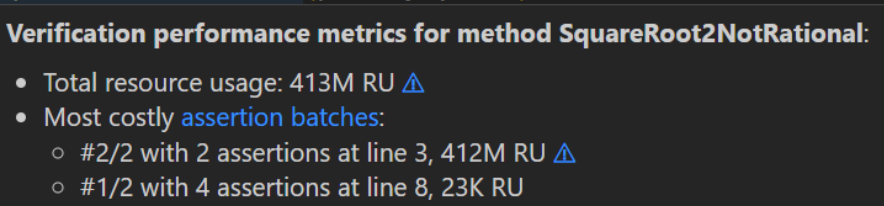

- On hovering the line containing the method name, if there are no other hovered assertions, I display a summary of verification as in Figure 4. This summary provides a link to the notion of assertion batches that helps splitting verification in smaller tasks, as well as a unicode warning icon

/!\with a link to documentation to fix verification when verification uses more than 10 million RU, a threshold I set by experience. - To identify which assertion batches are the slowest and need more work, especially when using the annotation

{:vcs_split_on_every_assert}, I displayed the top 3 most expensive assertion batches and line numbers.

Summary

I explained what can make someone need Dafny, how Dafny works, how gutter icons enhance the verification experience, how I designed the icons, and how I enhanced verification feedback using suitable hover messages. This, I believe, made the Dafny verification experience more accessible, more positive, and more enjoyable, for both new and existing users. The story is not finished, but I hope that you enjoyed this first chapter!

Acknowledgments

Adrianna Corona, for co-designing the icons and the user experience, while keeping the users’ needs in mind.

Aaron Tomb, for making positive versions of every error message and providing feedback on this post.

Ryan Emery, for being the first to ask me for gutter feedback à la Wallaby.js.

Remy Willems, for restructuring the back-end of the language server and for the numerous code reviews.

Clément Pit-Claudel, for reviewing the wording of the hover messages.

Robin Salkeld, for the discussion about displaying resource units and the design of {:vcs_split_on_every_assert}.

Rustan Leino, who inspired most of the content of the sections of Verification Debugging, which I wrote gradually after participating in sessions where he helped professional programmers.

Cody Roux, for the test and the first user quote.

Fabio Madge and Alex Chew, for providing feedback on this post.