Overview

Dafny verifies your program using a type of theorem prover known as a Satisfiability Modulo Theories (SMT) solver. More specifically, it uses the Z3 solver. In many cases, it’s possible to state only the final properties you want your program to have, with annotations such as requires and ensures clauses, and let the prover do the rest for you, automatically.

In other cases, however, the prover can need help. It may be that it’s unable to prove a particular goal, it may be that it takes so long to prove the goal that it slows down your development cycle, or it may be that the program successfully verifies one time but fails or times out after a small change to the program, a change in the Dafny version being used, or even a change in platform.

In all of these cases, the general solution strategy is the same. Although we hope that most Dafny users will not need to know much about the way Dafny’s verification goals are constructed or the way the SMT solver works, there are a few high-level concepts that can be very helpful in getting verification to succeed.

The most fundamental of these is that the solver works best when it has exactly the information it needs available to arrive at a particular conclusion. If key facts are missing, verification will certainly fail. If too many irrelevant facts are available in the scope of a particular goal, the solver can get lost pursuing fruitless chains of reasoning, leading to Dafny being unable prove the goal, timing out, or exhibiting a combination of verification success, timeout, and failure to prove the goal as small changes occur.

The second key concept is that certain types of facts are more difficult to reason about. These proofs can be helped by isolating the reasoning about such facts to small portions of your program and providing extra detail to help the prover when reasoning about those isolated instances. A later section describes some of the more difficult types of reasoning and provides some techniques for dealing with each.

Overall, this document provides a conceptual framework and examples of a number of concrete techniques for making verification in Dafny more likely to succeed, and to predictably succeed over time as the program and the Dafny implementation evolve. Fortunately, most of these techniques are closely connected to good software engineering principles such as abstraction and information hiding, and are therefore likely to make it easier for you to fully understand your program, and why it’s correct, as well.

At a high level, understanding how to optimize verification requires understanding a few things:

- what Dafny is attempting to prove, and what information is available in constructing a particular verification goal;

- which individual goals in the verification of a definition are difficult;

- what general types of verification tend to be difficult;

- how to provide additional hints to expand the information available for a specific goal; and

- how hide information to restrict the information available for a specific goal.

The facts Dafny deals with

To ensure that the verifier has exactly the right amount of information available, it’ll help to review exactly what information is in scope at a particular point in a Dafny program and what goals the verifier attempts to prove.

First, Dafny attempts to prove that several predicates are always true, including the following.

-

The expression in every

assertstatement, at the point where it occurs. -

The well-formedness condition of any partial operation, including array indexing and division, at the point where it occurs.

-

Every

invariantclause, before the loop it is associated with it begins, and at the end of each iteration of the loop body. -

Every

requiresclause of afunction,lemma, ormethod, at the call site. -

Every

ensuresclause of afunction,lemma, ormethod, right before returning.

A complete list is available here.

Although only one of these uses the assert keyword, we use the term assertion to describe each of these verification goals. A collection of assertions, taken together, is called an assertion batch.

When trying to prove each of these statements, Dafny assumes the following predicates to be true, making them available as facts for the verifier to use. These include the following.

-

Each

requiresclause of a Dafnyfunction,lemma, ormethod, is known, throughout the body, to hold at the beginning of the body. -

Each

invariantclause of a loop is known, throughout its loop body, to hold at the beginning of the body. -

Each

ensuresclause of a calledfunction,lemma, ormethodis known, for the remainder of the body calling it, to hold at the point just after a call site. -

The expression in each

assumestatement is known in subsequent code to hold at the point of the statement. -

The expression in each

assertstatement is known in subsequent code to hold at the point of the statement. -

The well-formedness condition of any partial operation, including array indexing and division, in subsequent code.

-

The branch condition for each branch, within the body of that branch.

In all of the above cases, “subsequent code” extends to the end of the current definition, except in the case of the assert P by S construct where it extends to the end of the by block. More detail on this construct appears later.

Because almost all of these facts are available in a limited scope, sometimes the body of a definition and sometimes specific blocks within that body, the structure of the program has a significant impact on the set of facts the solver considers when attempting verification. Restricting this set, by careful consideration of program structure, can significantly impact the performance and predictability of verification.

By default, whenever Dafny attempts to verify the correctness of a specific definition, it combines every assertion within that definition into a single assertion batch. This tends to provide very good performance in the common case, but sometimes it can slow down verification and make it difficult to identify which factors contribute to making the verification slow. To help identify the difficult assertions in a batch, and sometimes to speed up verification overall, it is possible to break verification up into a number of assertion batches, each containing a subset of all the assertions in the definition.

Identifying difficult assertions

When Dafny fails to prove an assertion, it will point out the location of that assertion in the program and describe what it was trying to prove at that point.

However, when verification times out, Dafny will (by default) tell you only which definition timed out. This is similarly true in the case where verification takes longer to complete than is practical for your development cycle. To get more fine-grained information about exactly which assertion was difficult to prove, it’s possible to tell Dafny to split the verification process into several batches, each of which can succeed, fail, or time out independently. This also makes independent statistics about resource use available for each batch.

Dafny provides several attributes that tell it to verify certain assertions separately, rather than verifying everything about the correctness of a particular definition in one query to the solver.

-

The

{:split_here}attribute on anassertstatement tells Dafny to verify all assertions leading to this point in one batch and all assertions after this point (or up to the next{:split_here}, if there is one) in another batch. -

The

{:focus}attribute on anassertorassumestatement tells Dafny to verify all assertions in the containing block, and everything that always follows it, in one batch, and the rest of the definition in another batch (potentially subject to further splitting due to other occurrences of{:focus}). -

The

{:isolate_assertions}attribute on a definition tells Dafny to verify each assertion in that definition in its own batch. You can think of this as being similar to having many{:focus}or{:split_here}occurrences, including on assertions that arise implicitly, such as preconditions of calls or side conditions on partial operations.

We recommend using {:isolate_assertions} over either of the other attributes under most circumstances. It can also be specified globally, applying to all definitions, with dafny verify --isolate-assertions. If you’re using the legacy options without top-level commands, use the /vcsSplitOnEveryAssert flag, instead.

When Dafny verifies a definition in smaller batches, the VS Code plugin will display performance statistics for each batch when you hover over a particular definition.

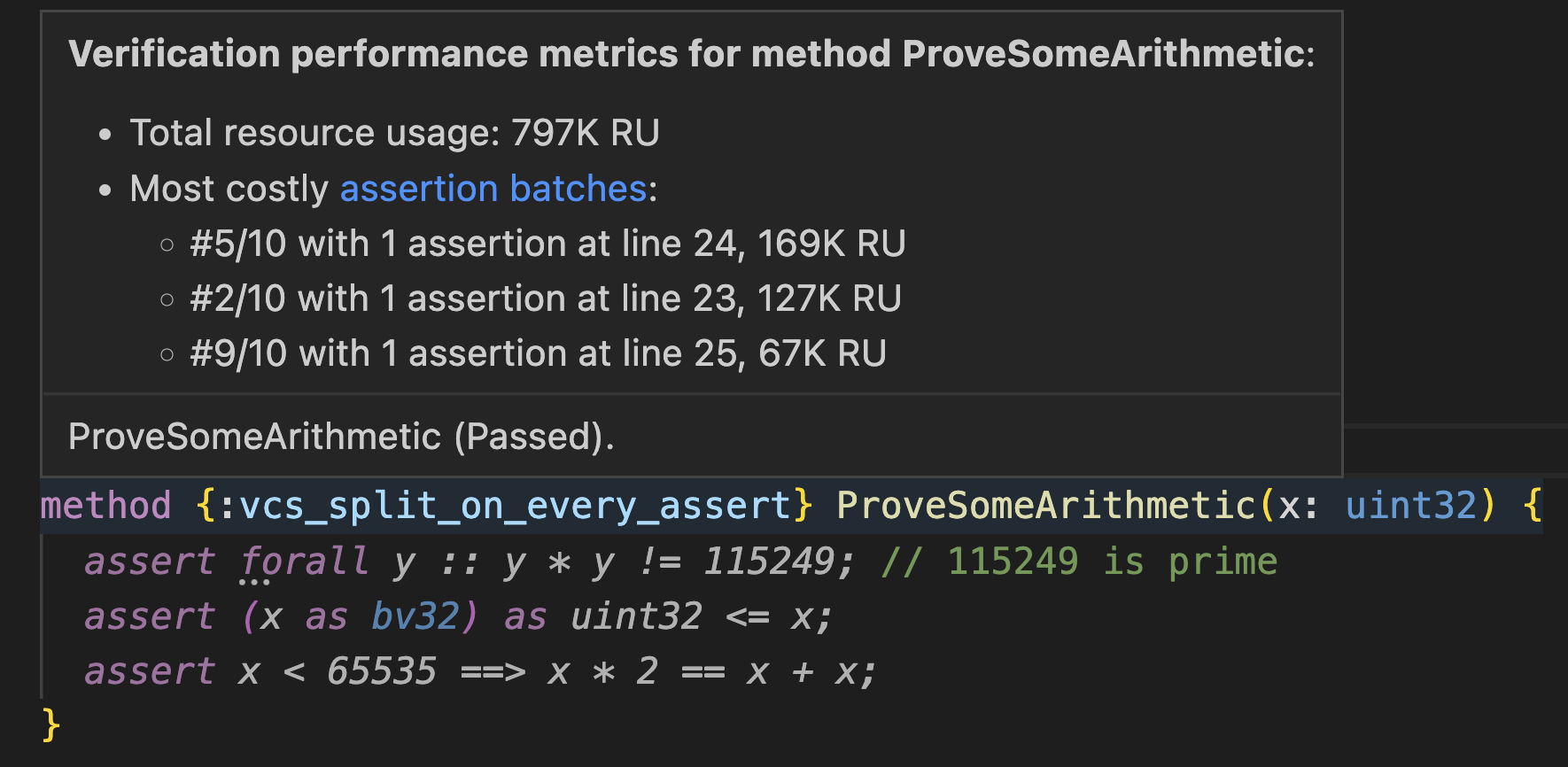

Consider the following method, which proves a few simple arithmetic facts.

const TWO_TO_THE_32: int := 0x1_00000000

newtype uint32 = x: int | 0 <= x < TWO_TO_THE_32

method {:isolate_assertions} ProveSomeArithmetic(x: uint32) {

assert forall y :: y * y != 115249; // 115249 is prime

assert (x as bv32) as uint32 <= x;

assert x < 65535 ==> x * 2 == x + x;

}

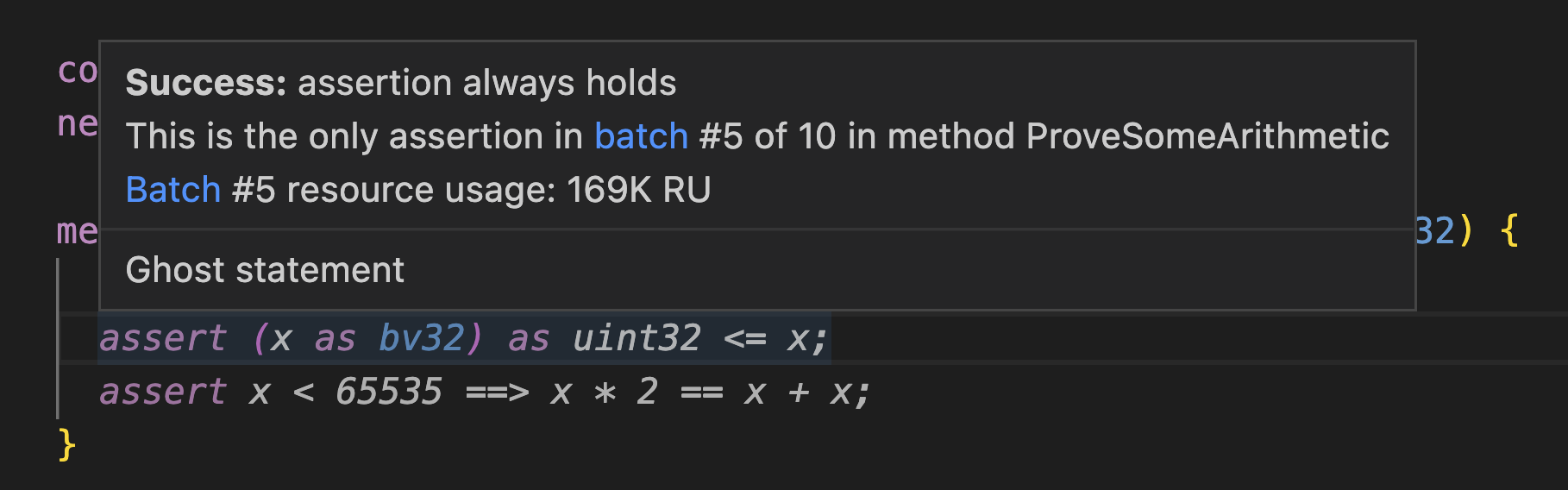

Hovering over the name of the definition will show you performance statistics for all assertion batches.

Although the time taken to complete verification is ultimately the factor that most impacts the development cycle, this time can depend on CPU frequency scaling, other processes, etc., so Z3 provides a separate measurement of verification difficulty known as a resource count. When running the same build of Z3 on the same platform multiple times, the resource count is deterministic, unlike time. Therefore, the IDE displays performance information in terms of Resource Units (RU).

Hovering over a specific assertion will show you performance statistics for the specific batch containing that assertion (and, in the case of {:isolate_assertions}, only that assertion).

Statistics are also available using command-line options, in formats optimized for either human or machine consumption. The --log-format text option to dafny verify, or the /verificationLogger:text old-style option, produces text to standard output. A snippet of the output for the method above might look something like this.

...

Assertion batch 4:

Outcome: Valid

Duration: 00:00:00.1344230

Resource count: 63182

Assertions:

ProveSomeArithmetic.dfy(6,22): result of operation never violates newtype constraints for 'uint32'

Assertion batch 5:

Outcome: Valid

Duration: 00:00:00.1359990

Resource count: 169237

Assertions:

ProveSomeArithmetic.dfy(6,32): assertion always holds

Assertion batch 6:

Outcome: Valid

Duration: 00:00:00.0844010

Resource count: 63494

Assertions:

ProveSomeArithmetic.dfy(7,14): result of operation never violates newtype constraints for 'uint32'

...

The --log-format csv option to dafny verify, or the /verificationLogger:csv old-style option, produces output in a file in CSV format, and prints the name of the file. For the above method, this file might look something like the following.

TestResult.DisplayName,TestResult.Outcome,TestResult.Duration,TestResult.ResourceCount

ProveSomeArithmetic (correctness) (assertion batch 1),Passed,00:00:00.1880600,50027

ProveSomeArithmetic (correctness) (assertion batch 2),Passed,00:00:00.1640300,127152

ProveSomeArithmetic (correctness) (assertion batch 3),Passed,00:00:00.1389720,59361

ProveSomeArithmetic (correctness) (assertion batch 4),Passed,00:00:00.1296620,63182

ProveSomeArithmetic (correctness) (assertion batch 5),Passed,00:00:00.1232840,169237

ProveSomeArithmetic (correctness) (assertion batch 6),Passed,00:00:00.0937380,63494

ProveSomeArithmetic (correctness) (assertion batch 10),Passed,00:00:00.0774500,66869

ProveSomeArithmetic (correctness) (assertion batch 9),Passed,00:00:00.0708400,67341

ProveSomeArithmetic (correctness) (assertion batch 8),Passed,00:00:00.0644100,64792

ProveSomeArithmetic (correctness) (assertion batch 7),Passed,00:00:00.0622940,65952

In all of these output formats, you can see that batch 5, corresponding to the assertion about conversion to and from bit vectors, is the most expensive to prove. Later sections will go into why this is the case, and how to make verification involving bit vectors more straightforward.

Identifying highly variable assertions

Sometimes, verifying a particular assertion succeeds initially but fails after a small change. We refer to this phenomenon as verification variability. The techniques in this document can help to fix verification when it occurs. However, sometimes it would be more helpful to predict when verification of your program is likely to be highly variable, and adapt it proactively, when you can intentionally set aside time, rather than needing to fix it retroactively.

Fundamentally, one key source of this variability comes from the fact that SMT solvers must make a sequence of initially arbitrary decisions to search through the space of possible proofs. To help explore this large space more effectively, they often use randomness to help decide between the arbitrary choices. In other cases, choices that are fundamentally arbitrary are made deterministically but in a way that is dependent on factors such as ordering within a data structure. The ordering of these internal data structures can be influenced by things like the names of definitions, the order in which they occur in a file, and so on.

Dafny can help you identify when the verification of a particular assertion may begin to fail after small modifications if you use the measure-complexity command. When using this command, Dafny attempts to verify each definition in your program multiple times, each time with a different random seed. This seed is used to permute the names and ordering used in formulas sent to the solver, and then is given to the solver to use in making its own random decisions internally.

If the time or resource count taken to verify a given assertion batch is higher than most, this is frequently predictive of later failure after small modifications. Similarly, if this cost varies widely depending on the random seed, it can also point to high underlying complexity.

To measure the variation in resource use for the method from the previous section, on 10 different random seeds, we could use the following command.

$ dafny measure-complexity ProveSomeArithmetic.dfy --log-format csv --iterations 10

This will produce a CSV file and print out its name, as in the previous dafny verify case. With the measure-complexity command, however, each assertion batch will appear multiple times in the file. Given a CSV report containing the results of multiple iterations of verification, the dafny-reportgenerator tool can perform statistical analysis on this data, and can even be used to fail a build if the statistics exceed specified bounds.

We generally recommend keeping the coefficient of variation (a.k.a. normalized standard deviation) of the resource count under 20%, and setting some (generally project-dependent) limit on total resource count. This can be enforced with the following command.

$ dafny-reportgenerator summarize-csv-results --max-resource-cv-pct 20 --max-resource-count 200000 some-file.csv

On CSV file generated from the above example, you might get output like the following.

...

Some results have a resource coefficient of variance over the configured limit of 0.20:

ProveSomeArithmetic (correctness) (assertion batch 5): resource coefficient of variance = 0.47275460664050895

Errors occurred: see above for details.

Here we can see that the assertion identified as the most expensive in the previous section also has the highest variability. The exit code from dafny-reportgenerator will be 1 in this case, since 0.47 is higher than 0.20, so it can be used to fail a build or CI job.

Types of assertion that can be difficult to verify

Several specific types of operation may make Dafny programs particularly difficult to verify. Verifying assertions that involve these operations can be very slow, or even impossible, without additional help in the form of intermediate assertions or lemmas.

Non-linear arithmetic

Non-linear arithmetic in Dafny generally takes the form of multiplication operations where both sides are variables or any instance of the division or modulus operations. Proving arbitrary facts about operations of this form is undecidable, so the solver must use incomplete heuristics, and frequently gives up.

Fortunately, Dafny gives you the power to prove complex facts about non-linear arithmetic by building on slightly less complex facts, and so on, down to the point where the solver can prove the smallest building blocks automatically.

There are a number of examples in the Dafny libraries repository that do just this. For example, consider the following sequence of lemmas that builds up from basic properties about multiplication all the way to basic properties about exponentiation.

lemma LemmaMulBasics(x: int)

ensures 0 * x == 0

ensures x * 0 == 0

ensures 1 * x == x

ensures x * 1 == x

{

}

opaque function Pow(b: int, e: nat): int

decreases e

{

if e == 0 then

1

else

b * Pow(b, e - 1)

}

lemma LemmaPow0(b: int)

ensures Pow(b, 0) == 1

{

reveal Pow();

}

lemma LemmaPow1(b: int)

ensures Pow(b, 1) == b

{

calc {

Pow(b, 1);

{ reveal Pow(); }

b * Pow(b, 0);

{ LemmaPow0(b); }

b * 1;

{ LemmaMulBasics(b); }

b;

}

}

All of these lemmas can be proved and used with the --disable-nonlinear-arithmetic flag enabled. These lemmas also demonstrate several techniques that we’ll describe in more detail later: lots of small lemmas, opaque functions, and calc statements.

If you have a difficult non-linear fact to prove, and proving it from the ground up is infeasible, it is possible, as a last resort, to adjust how Z3 attempts to prove arithmetic formulas. It contains a parameter, smt.arith.solver, that allows you to choose between one of six different arithmetic decision procedures. Dafny has historically used solver “2”, and continues to do so by default. This peforms most effectively on the corpus of examples that we have experimented with. However, solver “6”, which is the default for Z3 when not being invoked from Dafny, performs better at non-linear arithmetic. Currently, it’s possible to choose this solver using the Dafny flag --boogie /proverOpt:O:smt.arith.solver=6 (or just /proverOpt:O:smt.arith.solver=6, when not using top-level commands).

Relationships between integers and bit vectors

Dafny contains two distinct ways to describe what might be stored in a machine word in other programming languages.

-

The

inttype denotes the unbounded mathematical integers. A newtype based onintcan be used to represent the subset of integers that can be stored in a machine word of width n. -

The

bvn type denotes bit vectors of width n, which can be used to represent a subset of $2^n$ of the integers.

Mathematical operations such as addition and multiplication are available for both types. Bit-wise logical and shifting operations are only available for bit vectors. The as keyword can be used to convert between integers and bit vectors, assuming that Dafny can prove that all possible values of the original type can be represented in the new type. However, this conversion is described, at the logical level used for verification, as a complex non-linear equation. Therefore, reasoning in which Dafny must consider the relationship between facts about a value represented as an integer and other facts about that value represented as a bit vector will typically be harder than when reasoning purely about integers or purely about bit vectors.

For example, consider the following three lemmas.

const TWO_TO_THE_32: int := 0x1_00000000

newtype uint32 = x: int | 0 <= x < TWO_TO_THE_32

lemma DropLSBLessBV(x: bv32)

ensures (x & 0xFFFFFFFE) <= x

{}

lemma DropLSBLessAsBV(x: uint32)

ensures ((x as bv32) & 0xFFFFFFFE) <= x as bv32

{}

lemma DropLSBLessIntBVLemma(x: uint32)

ensures ((x as bv32) & 0xFFFFFFFE) as uint32 <= x

{

assume false;

}

These all show that clearing the least significant bit of a 32-bit word results in a value less than or equal to the original. The first lemma operates purely on bit vectors, whereas the second starts with an integer constrained to be in the range representable in a 32-bit integer. Although Dafny is able to prove both both, proving the latter, with Dafny 4.0.0 and Z3 4.12.1, takes around 7x the resource count of the former (and about twice as much time). The third requires reasoning about the relationship between the result of a bit vector operation and its value as an integer, and Dafny is unable to prove this variant at all (hence the assume false in the body of the lemma, to allow automatic checking of the examples in this document to succeed).

A wiki page providing more detail on optimizing bit-vector verification is available here.

Quantified statements

Dafny allows arbitrary use of quantifiers in logical formulas. It’s possible to, for example, write forall x: int :: exists y: int :: y > x. From a technical standpoint, this means it allows you to write arbitrary statements in first-order logic. However, the problem of deciding the validity of a given statement in first-order logic is undecidable. And, in practice, heavy use of quantifiers, while it is often the most natural way to describe a program, can lead solvers such as Z3 to time out or give up when trying to verify your program.

Typically the solution is not to avoid quantifiers altogether. Dafny can be very good at reasoning about them in resticted contexts. Instead, it tends to be good to follow two general principles:

-

Give Dafny help instantiating quantifiers when using quantified statements to prove other things. This will typically involve intermediate assertions, as described in the next section.

-

Restrict the scope of quantifiers as much as possible. Perhaps use them in certain definitions, but then use the fully-quantified versions of those definitions only to prove less-heavily-quantified facts you may use later. Or encapsulate quantified formulas in opaque predicates that are usually used just by name and only occasionally revealed. Later sections will describe these techniques in more detail.

Adding intermediate steps

For verification to succeed, the verifier must have enough information available. For verification to be efficient and predictable, it must not have too much information available, but it also helps to not require it to make overly large deductive leaps. For verification to be maintainable in the long term, therefore, it’s important to find the right balance.

In many cases, this can be done in two phases.

-

First, determine a sufficient set of facts to allow a goal to be verified. Once it has passed the verifier once, you can be confident that the goal is valid, and that it’s possible to prove its validity using the facts at hand.

-

Second, trim down the set of irrelevant facts available, or add intermediate steps in an isolated context, to optimize the verification process.

We’ll start by focusing on how to add information to allow verification to go through. Some of these steps can also speed up verification that already succeeds, but they can also slow it down. So, after we describe how to add information to the verification proces, we continue by showing how to isolate the information needed to verify a particular fact, hiding it in the context of verifying other facts.

Inline assertions

Sometimes, when you know A and want to prove C, Dafny is unable to make the logical leap directly. In these cases, it’s often the case that there’s some predicate B for which Dafny can prove both A ==> B and B ==> C automatically. When that’s true, inserting an assert B statement in the right place can allow verification to go through.

This example, modified from some code in the libraries repository, illustrates the case. It shows that if a given binary operator (passed in as a function value) has a left unit value and a right unit value that those two unit values are equal to each other.

ghost predicate IsLeftUnital<T(!new)>(bop: (T, T) -> T, unit: T) {

forall x :: bop(unit, x) == x

}

ghost predicate IsRightUnital<T(!new)>(bop: (T, T) -> T, unit: T) {

forall x :: bop(x, unit) == x

}

ghost predicate IsUnital<T(!new)>(bop: (T, T) -> T, unit: T) {

&& IsLeftUnital(bop, unit)

&& IsRightUnital(bop, unit)

}

lemma UnitIsUnique<T(!new)>(bop: (T, T) -> T, unit1: T, unit2: T)

requires IsUnital(bop, unit1)

requires IsUnital(bop, unit2)

ensures unit1 == unit2

{

assert unit1 == bop(unit1, unit2);

}

Here, UnitIsUnique couldn’t be proved automatically (with a { } body), but succeeds easily with the intermediate assertion.

Calculation statements

When there are many intermediate assertions needed to get from A to C, it can become messy and difficult-to-read if they exist only as a sequence of assert statements. Instead, it’s possible to use a calc statement to chain together many implications, or other relationships, between a starting and ending fact. The version of UnitIsUnique that exists in the libraries repository is actually proved as follows.

lemma UnitIsUnique<T(!new)>(bop: (T, T) -> T, unit1: T, unit2: T)

requires IsUnital(bop, unit1)

requires IsUnital(bop, unit2)

ensures unit1 == unit2

{

calc {

unit1;

== { assert IsRightUnital(bop, unit2); }

bop(unit1, unit2);

== { assert IsLeftUnital(bop, unit1); }

unit2;

}

}

Here, the calc block establishes a chain of equalities, unit1 == bop(unit1, unit2) == unit2 by using an intermediate assertion to justify each step. This is more information than Dafny strictly needs, but can make the code more readable and the verification less variable.

Instantiating universally quantified formulas

A universally quantified formula tells you that a certain fact is true for all values of a variable in a given domain. In many cases, however, you may know more about what specific instances need to be proved.

Dafny can often bridge the gap between a universally quantified fact and an unquantified fact needed to make progress. However, it needs to do much less work if you can describe specific instantiations of interest.

For example, an old commit in the libraries repository contains the following snippet:

lemma LemmaMulEqualityAuto()

ensures forall x: int, y: int, z: int {:trigger x * z, y * z } :: x == y ==> x * z == y * z

...

LemmaMulEqualityAuto();

assert sum * pow == (z + cout * BASE()) * pow;

The assertion helps Dafny figure out how to instantiate the postcondition of LemmaMulEqualityAuto, making the verification process more efficient.

As we’ll describe in more detail later, however, it can sometimes be better to avoid the quantifiers in the first place than to help Dafny instantiate them.

Hiding information

There are several ways to structure a Dafny program to limit the number of facts that are available in scope at any particular point. First we’ll go over a few that can be applied as small changes to existing programs, and then we’ll cover some that are better applied early in the development process (though they can be applied to existing programs with more significant refactoring).

Local proofs

On the other hand, and more frequently in practice, a sequence of assertions will build on each other, constructing a path from some initial fact to a final conclusion. If the initial assertions exist only to prove the final one, and they are not relevant for any other proofs, they can be hidden with the assert ... by { ... } syntax.

For example, say you have the following code.

assert A; // Something readily provable on its own

assert B; // Something readily provable on its own

assert C; // The conclusion you really care about, which is easier to to prove given knowledge of A and B

You can restructure this as follows.

assert C by {

assert A;

assert B;

}

This makes C visible in subsequent code, but hides A and B except when proving C.

Proofs in lemmas

If you find yourself asserting many things in sequence, including in a calculation block, consider moving that proof to a separate lemma and calling it at the point where you need the final conclusion. Consider the same example from the previous section.

assert C by {

assert A;

assert B;

}

This can be moved to a separate lemma.

lemma CIsTrue()

ensures C

{

assert A;

assert B;

}

Then CIsTrue can be called from any location where you need to know C. In practice, CIsTrue will probably need to take parameters, to account for any free variables in C, and those must then be passed in at any call site. This can make proofs somewhat more verbose, at a local level, but if done carefully it can reduce the total size and complexity of a program.

Opaque definitions

By default, the body of a function definition is available to the verifier in any place where that function is called. The bodies of any functions called from this initial function are also available. Stated differently, Dafny inlines function bodies aggressively during verification. There are two exceptions to this.

-

The body of a function (or predicate) declared with the

opaquekeyword is, by default, not available to the verifier. Only its declared contract is visible. In any context where information about the body is necessary to allow verification to complete, it can be made available withreveal F();for a function namedF. -

The body of a recursive function is normally available to depth 2 when it appears in an asserted predicate or depth 1 when it appears in an assumed predicate. That is, the body of the function and (in the assertion case) a second inlining of its body at each recursive call site are available to the verifier. The

{:fuel n}annotation will increase the depth to which recursively-called bodies are exposed.

Aggressive inlining is convenient in many cases. It can allow Dafny to prove quite complex properties completely automatically. However, it can also quickly lead to feeding an enormous amount of information to the verifier, most of it likely irrelevant to the goal it is trying to prove.

Therefore, it can be valuable to think carefully about which aspects of a function need to be known in each use case. If it’s possible to structure your program so that each caller only needs information about certain aspects of its behavior, it can be valuable to do the following:

-

Add the

opaquekeyword to the function definition. -

Reveal the definition only in the cases where its body is necessary.

-

Potentially prove additional lemmas about the function, each of which may reveal the function during its own proof but allow its callers to leave the function body hidden.

The following is an in-depth example of using this technique.

datatype URL = URL(scheme: string, host: string, path: string) {

opaque predicate Valid() {

scheme in { "http", "https", "ftp", "gopher", "mailto", "file" }

}

opaque function ToString(): string

requires Valid()

{

scheme + "://" + host + "/" + path

}

static function Parse(text: string): (url: URL)

ensures url.Valid()

}

function CanonicalURL(urlString: string): string {

var url := URL.Parse(urlString);

url.ToString()

}

This code declares a data type to represent a (simplistic) URL, and includes a Valid predicate that describes what it means to be a valid URL. The ToString function will convert a valid URL, and the Parse function (unimplemented for now) constructs a valid URL (putting aside the possibility of a parsing failure for the moment). Using this data type, the CanonicalURL function turns a URL string into its canonical equivalent. From the point of view of the implementation of this function, it doesn’t matter what Valid means. It only matters that Parse returns a valid URL and ToString requires one. When Valid is opaque, Dafny ignores its definition by default, simplifying the reasoning process. It’s easy to conclude url.Valid() from url.Valid() without knowing what Valid means.

In this case, no reveal statements or auxiliary lemmas are necessary.

Although the difference is small in this simple case, we can already see a performance impact of making Valid opaque. In one example run, using Dafny 4.0.0 and Z3 4.12.1, the code above verifies using 83911 RU (taking 0.282s). An equivalent example, in which Valid and ToString are not opaque, takes 87755 RU (and 0.331s). For larger programs with larger functions, especially with deep function call stacks, the difference can become much larger.

In the context of larger programs, you can enforce opacity even more strongly by using export sets. If you write lemmas declaring the key properties of each of your functions that are relevant for client code, you put those functions and lemmas in the provides clause of your module, and very little if anything in the reveals clause. If you do this, it’s important that you provide lemmas covering all the important behavior of your module. But, if you do, then it becomes easier for developers to write client code that uses your module, and easier for Dafny to prove things about that client code.

Making definitions opaque can be particularly important when they are recursive or involve quantifiers. Because of the considerations around quantifiers described earlier, hiding quantified formulas until they’re needed can be very important for improving performance and reducing variability.

Opaque specification clauses

In addition to top-level definitions, assertions, preconditions, postconditions, and loop invariants can be made opaque. If you add a label to any instance of one of these contstructs, it will be hidden by default and only available when explicitly revealed.

For example, consider the following method with an opaque precondition.

method OpaquePrecondition(x: int) returns (r: int)

requires P: x > 0

ensures r > 0

{

r := x + 1;

assert r > 0 by { reveal P; }

}

Subsumption

The default behavior of an assert statement is to instruct the verifier to prove that a predicate is always true and then to assume that same predicate is true in later portions of the code, making it available to help prove other facts. This is called subsumption.

On occasion, however, you may have an assert statement that exists to show a desired condition for its own sake, and that does not help prove later facts. This might occur during the intermediate stages of the development of a verified program in which you want to establish some intermediate facts locally, which you believe to be indicative of correctness, but don’t yet want to expand these into fully-fledged contracts on your definitions that could be used to establish a more global notion of correctness.

In this case, you can disable subsumption, using assert {:subsumption 0} P, to reduce the number of facts in scope in subsequent code. This is similar to assert L: P, except that in the case of a labeled assertion the predicate can be selectively revealed later. If you know you’ll never need P, rather than usually not needing it, subsumption could be a better option.

Avoiding quantifiers

Dafny allows you to prove both quantified and unquantified version of a fact. And, in some cases, the quantified version can be more convenient, allowing you to prove things with fewer steps, and with less need to keep track of details. For example, the Dafny libraries repository contains a definition that looks roughly like the following (with a few simplifications).

lemma LemmaMulAuto()

ensures forall x:int, y:int :: x * y == y * x

ensures forall x:int, y:int, z:int :: (x + y) * z == x * z + y * z

ensures forall x:int, y:int, z:int :: (x - y) * z == x * z - y * z

{

...

}

lemma LemmaMulIsDistributiveAddOtherWay(x: int, y: int, z: int)

ensures (y + z) * x == y * x + z * x

{

LemmaMulAuto();

}

However, although these proofs are very succinct, they require the verifier to do more work. If you encounter cases where this leads to verification failures, it can often help to prove more specific instances.

One particular pattern that works well when creating general-purpose lemmas proving universal properties is to prove a parameterized version first and then use that to prove the universal version. Then, clients of the lemma can choose one or the other.

For example, consider the following two lemmas taken from the libraries repository.

lemma LemmaMulEquality(x: int, y: int, z: int)

requires x == y

ensures x * z == y * z

{}

lemma LemmaMulEqualityAuto()

ensures forall x: int, y: int, z: int :: x == y ==> x * z == y * z

{

forall (x: int, y: int, z: int | x == y)

ensures x * z == y * z

{

LemmaMulEquality(x, y, z);

}

}

There was another instance of code in the repository where verification began to fail after upgrading the version of Z3 included with Dafny. That code originally used LemmaMulEqualityAuto. We updated it to call LemmaMulEquality with the appropriate parameters and verification reliably succeeded.

In general, creating and using explicit lemmas like LemmaMulEquality, and skipping lemmas like LemmaMulEqualityAuto altogether, tends to lead to code with less verification variability.

Adding triggers

If you can’t avoid the use of quantifiers, careful use of triggers can help reduce the amount of work Dafny needs to do to benefit from the information in a quantified formula. The original version of the LemmaMulEqualityAuto lemma in the above looks like the following.

lemma LemmaMulEquality(x: int, y: int, z: int)

requires x == y

ensures x * z == y * z

{}

lemma LemmaMulEqualityAuto()

ensures forall x: int, y: int, z: int {:trigger x * z, y * z } :: x == y ==> x * z == y * z

{

forall (x: int, y: int, z: int | x == y)

ensures x * z == y * z

{

LemmaMulEquality(x, y, z);

}

}

The {:trigger} annotation tells it to only instantiate the formula in the postcondition when the solver sees two existing formulas, x * z and y * z. That is, if it sees two multiplications in which the right-hand sides are the same.

Adding an explicit trigger annotation is generally a last resort, however, because Dafny attempts to infer what triggers would be useful and typically comes up with an effective set. The need for manually-specified triggers often suggests that code could be refactored into a larger number of small, separate definitions, for which Dafny will then infer exactly the triggers you need.

Smaller, more isolated definitions

As a general rule, designing a program from the start so that it can be broken into small pieces with clearly-defined interfaces is helpful for human understanding, flexibility, maintenance, and ease of verification. More specific instances of this include the following.

-

Break large functions into smaller functions, especially when they’re ghost functions, and make at least some of them opaque. I often consider a ghost function of more than a handful of lines to be a bad code smell. There are exceptions where larger functions are necessary or are the most straightforward alternative, though, such as when handling all of the many cases of a complex algebraic data type.

-

Prove lemmas about functions rather than having numerous or complex postconditions. The individual lemmas can then be invoked only when needed, and other facts that are true but irrelevant will not bog down the solver.

-

Break methods up into smaller pieces, as well. Because methods are always opaque, this will, in many cases, require adding a contract to each broken-out method. To make this more tractable, consider abstracting the concepts used in those contracts into separate functions, some of which may be opaque.

Verification fine-tuning

Conjunction vs. Nested ifs

We have witnessed cases where the following code:

if (a && b) {

assert true;

}

verifies slower than

if (a) {

if (b) {

assert true;

}

}

This is because the well-formedness of && b adds an extra proof obligation, which is empty in this case but not trimmed, so there is an extra if (a) {} in the encoding.

Therefore, for verification performance, the nested ifs could verify faster, and we have witnessed one case where it does. In other cases, this difference in translation might trigger butterfly effects and uncover brittleness.

Summary

When you’re dealing with a program that exhibits high verification variability, or simply slow or unsuccessful verification, careful encapsulation and information hiding combined with hints to add information in the context of difficult constructs is frequently the best solution. Breaking one large definition with extensive contracts down into several, smaller definitions, each with simpler contracts, can be very valuable. Within each smaller definition, a few internal, locally-encapsulated hints can help the prover make effective progress on goals it might be unable to prove in conjunction with other code.

Some of the key concrete techniques to limit the scope of each verification goal include:

- Making functions and predicates

opaquewhen possible. - Moving a sequence of assertions that build on each other into an

assert P by { ... }block, wherePis the final conclusion you want to establish. - Making contract elements and assertions opaque, using labels, when you can’t conveniently abstract their contents into separate definitions.

- Avoiding quantifiers when possible, and encapsulating them in opaque definitions when they can’t be avoided.

- Using additional parameters to lemmas instead of quantified postconditions.

- Separating reasoning about difficult-to-combine data types such as integers and bit vectors.

Within each smaller definition, techniques for providing hints include:

- Using inline assertions.

- Instantiating any quantified statements by hand.

- Providing detailed chains of reasoning for any statements about non-linear arithemetic.

- Using

calcstatements instead of long chains ofassertstatements.